FRIDAY, May 1, 2020: NOTE TO FILE

A Life in Question

The short of it

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: QUESTION EVERYTHING, FROM THE WIRES, BELIEVE NOTHING

Abstract: Isaac Asimov managed to keep his memoirs to under four readable volumes. I can at least aspire to keep mine under three pages, even if unreadable. But it took even him more than a day to write his, so I have some bragging rights. For the first time ever, I became a published author: AmigaLove. If busy minds matter, a shorter alt memetic bio is added.

TUCSON (A-P) — I was an exceptionally dull and stupid child, hence no efforts were made to educate me. I learned early on that asking adults questions annoyed them, so I stopped. And the other kids didn't 'know shit from apple butter', so I didn't ask them either. This condition favored my becoming an autodidact having a fool for a teacher.

Evidence is that I developed at an exceptionally slow rate. In any large population of ten year-olds, some may be functionally more like seven year-olds and some could pass for a teenager. In childhood the gap between my developmental 'age' and the development of my cohorts widened until puberty, after which their rate of growth slowed, but my rate of maturation didn't slow, which allowed me to catch up with my chronological peers. Or exceed them. I was 25 when people stopped asking me which high school I went to.

Evidence is that I developed at an exceptionally slow rate. In any large population of ten year-olds, some may be functionally more like seven year-olds and some could pass for a teenager. In childhood the gap between my developmental 'age' and the development of my cohorts widened until puberty, after which their rate of growth slowed, but my rate of maturation didn't slow, which allowed me to catch up with my chronological peers. Or exceed them. I was 25 when people stopped asking me which high school I went to.

I was actually in high school when for some reason, having been a non-reader, I tried to read Walden, and Thoreau noted that he only needed to work six weeks a year to support himself the rest. So why should I need to work more? In my last year of public schooling I managed two 'A's, a miracle of rare device, one in zoology and one in earth science. I was becoming more functional.

After high school I spent summers 'on the road' as a migrant farmworker putting in my six weeks. I went to a community college for three years: first year mostly 'C's, second 'B's, and third mostly 'A's. It was low cost schooling and I lived in the back of a 1954 Ford pickup I bought for $200 and had fashioned a five-sided box from plywood on. Summers began by hitchhiking to Bakersfield to chop cotton, then following the crops north by hitchhiking and riding freight trains. It was a wonderful life.

Cheap as schooling was, I decided to 'drop out' and feed directly from the trough of knowledge, libraries, so I moved to Isla Vista, a student ghetto next to the University of California Santa Barbara whose nine-story library was open until 11 pm. For nine months or so I wandered the stacks in wonder and read books, whatever seemed of interest. I often walked on the beach and occasionally took in presentations offered. Especially memorable was an informal talk with students (or whomever showed up) given by Garrett Hardin. I wasn't a real student so I didn't presume to speak to or socialize with any. I once lost my voice from months of disuse (I don't even move my lips when I read). Some seven years passed.

I was on my way back to California, end of season that had ended with picking apples near the Canadian border. I was watching the Oregon countryside pass from an open boxcar when I thought that if I became an agricultural expert I could live elsewhere about the world and serve humanity by furthering the Green Revolution.

I tended to work more than six weeks a year, so I had saved up on the money stuff each year. It paid my way to Cal Poly State University SLO for three years and I took BS degrees in soil and crop science (late 1970s and schooling was still cheap).

I did well, would have been paid to go to graduate school, but my education, if not my schooling, had informed me that as an expert in agronomy all I could do was show others how to turn fossil fuel inputs, direct and indirect, into food. But doing so was not sustainable, so transitioning traditional people from what works to industrial agriculture that could produce ten times more food (for a time while supporting ten times more people) was not in their best long-term interest. So I never used my degrees to serve the global economy or make money or otherwise save the world as pretending to save the world or be a benefactor of humankind was of no interest.

After graduating with highest honors I worked another summer as an overeducated farmworker. It was a last hurrah and I decided to move on as, not unlike Thoreau, I had other lives to live. My older brother knew an engineer who had one of the new Commodore 64 computers. I soon had one too. Not much use without software, so I started typing in BASIC programs published in magazines. I learned BASIC and got into coding to implement visions of software derring-do like a version of 'Guess the Animal—Are you thinking of an animal?' with questions based on taxonomy such that most common animals could be guessed and players could add new ones. I became active in CSUN (a local user group, the Commodore Systems User Network). I served as 'disk of the month' compiler, and, yes, I shared my latest offerings. For a year I was newsletter editor. I got a 300 BAUD modem and went online before there was a WWW.

I even got a 'real' job as an instructional assistant to a special ed teacher in the public school system. I set up a C64 system in the class. California had just decided to levy a tax on the innumerate (the State Lottery) and so I wrote an accurate simulation and each student who played got a few hundred in pretend money to 'win' more pretend money. None did, and when their bank account was empty I refilled it, but only after they stood on one leg with a book on their head while they recited a poem from memory. Now that's education.

One year of real work was enough and while gainfully employed I had gone to a teacher's conference where vendors were plying their wares. I saw a talking word processor for the Apple II for maybe $300 or some ridiculous amount and I thought I could write one for the C64 and sell it for $5. And I did. But first I had to think about what a word processor should do. I knew plenty of software collectors (pirates) and was one, so I looked at the offerings and envisioned one I would want to use (then make it talk).

I went to live on the streets of Santa Barbara California, parking next to a city park across from an apartment complex where I wasn't taking anyone's accustomed parking space. My home on wheels looked like a utility shell (a new one on a '65 Chevy pickup) and appeared to be locked with a small padlock from the outside such that surely no one could be inside. Flying under everyone's radar worked. I had a small bicycle that fit in the front passenger side. I rode to the beach most mornings, ran a few miles, then took a swim in the ocean before doing the lay-on-the-beach thing. Back at the truck, I lugged my portable C64 to the city library and did a day's work.

To realize my vision I had had to seriously learn assembly language. It ended up taking an hour and a half to assemble a new version, but there were books to read and I often just left the computer running in the library and went for a walk about the city. So some hours of coding and bug hunting, then a break. This went on for a full year. I had to document the software and managed to get a 24-pin printer running in the back of my truck off an inverter to produce a proof of a manual to be copied.

I can't say I had no idea what to do with the heir of my invention, because I did. There were hundreds of Commodore user groups worldwide and I had a list I could type in, so I did. I made a demo disk that did everything but save. I used all but a hundred and some dollars of my life's savings to send out the demo disks. That could have been the end of the story, but it turned out not to be. Go figure.

I offered to supply user groups with a master copy, numbered disk labels, and manuals (even keyboard overlays) for not much for 10, and less per each on up to 50. I got orders. The Bartlesville Commodore User Group ordered 50 as a first order. The group, of course, would add a copy fee, so, win-win, my 'userware' innovation worked.

To provide user support I'd need one of those telephone things, so I moved into one of those house things my parent's owned as a rental, a small place behind the main rental. Apart from the kitchen, which became the shipping department, I kept on coding in the bedroom until I couldn't, then I'd slide out of my seat to sleep on the floor in my sleeping bag.

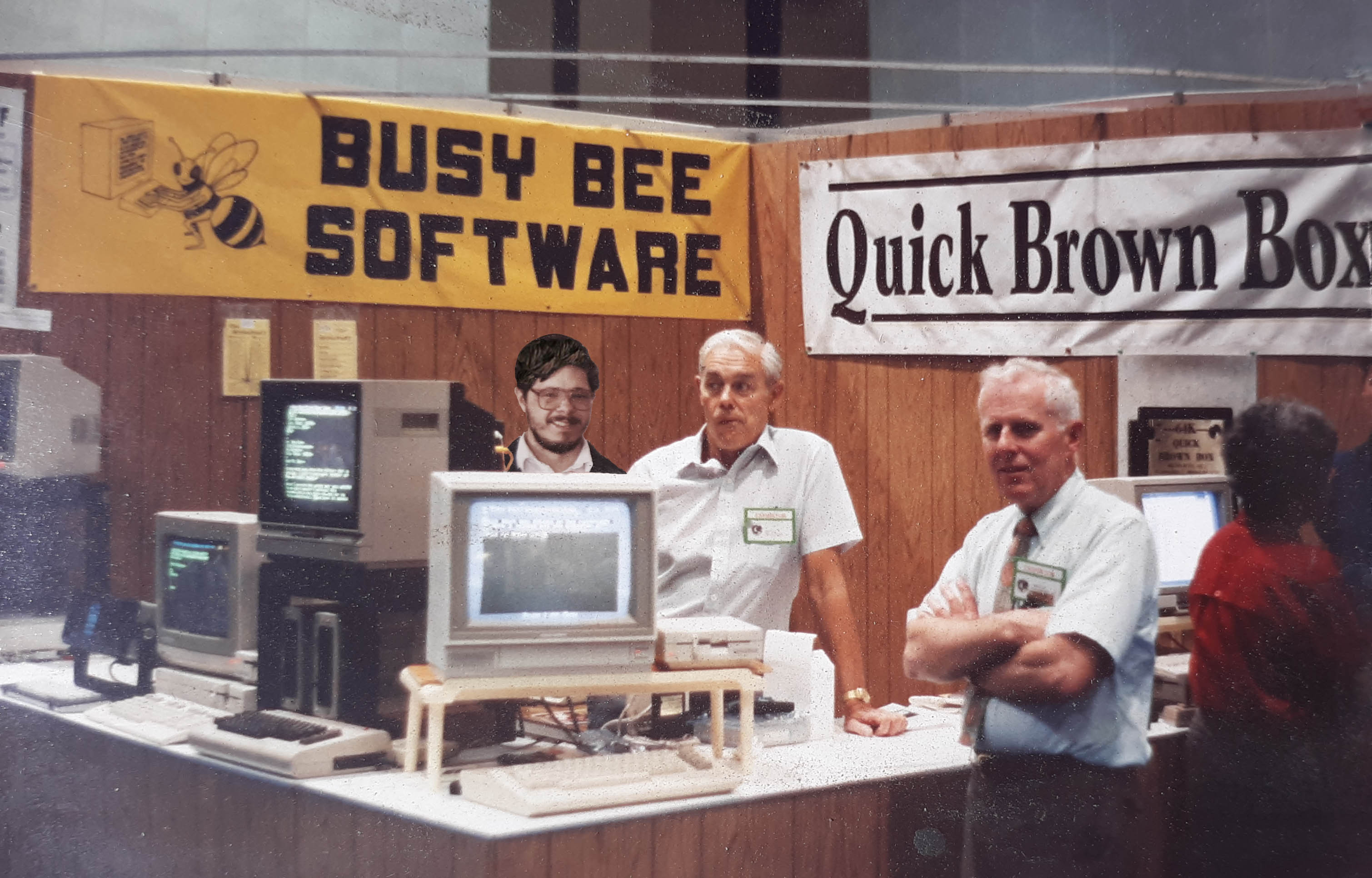

Sometimes I'd awake to a ringing phone and someone seeking user support would get all annoyed because I obviously wasn't actually awake yet. My parents lived next door and my dad was my only accomplice who filled most of the orders. I had never made enough money to pay taxes so he handled that for me. I was in business for maybe seven years total. At the peak (and there always is one), sales were over $70K/year and I flew in an airplane thing to Philadelphia for a Commodore Convention. I did another in LA. Things happen. Go figure.

Me, my dad, and Brown.

I ended up president of CSUN, as some people are easily impressed. I offered free Commodore systems user support and was starting to look like a normal person. One user married me for lifetime user support. We are still tying the knot. Things happen and I can't figure it out, so I just dance with the system.

I've had a few other real jobs (one lasted seven years), but nothing to speak of. Properly unemployed again, I'm working now to save the world (aka humanity from itself), but no one is paying me to. I've never worked for money in my life. Sometimes it came my way, but it was only incidental to doing important things, like chopping cotton or picking apples.

M. King Hubbert noted while giving a seminar at MIT's Energy Lab in 1981 that there are two incompatible cultures: the 'monetary culture' and the 'matter-energy systems' worldview. I live in Hubbert's world. All the rest of you Anthropocene enthusiasts don't. But have a good Anthropocene while you can. It's a wonderful life while it lasts. It is down right mysterious. I wonder why?

Alt Memetic Bio

POVs happen and I seem to have one:

Basically humanity got the 'Houston, we have a problem' message by 1980 when Catton published 'Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change' summarizing the prior three decades of what Nature was telling those who listen about the human problematique following the start of the Great Acceleration.

Meanwhile 'the pace of planetary destruction has not slowed' [to quote David Suzuki from his 80th birthday email to supporters]. No point in repeating the 'we have a problem' meme and expect a different outcome.

The next step for those having astronaut concerns, soon after a bit more information of what the problem was, was for NASA scientists and engineers to come up with a short list of viable solutions and pick one, then make it so. Doing so now would be adaptive, perhaps enabling humanity to be not only an adaptive, dissipative structure, but an evolvable system as well. Asking politicians for 'solutions' or religious leaders to pray for the astronauts would have ensured their death as it will for most humans currently feeding from the trough of industrial society. [And sorry about that in advance.]

“Thought makes the whole dignity [potential value] of man; therefore endeavor to think well, that is the only morality.” — Blaise Pascal

"Ehrfurcht vor dem Leben" [Venerate all Life]

"Thought cannot avoid the ethical or reverence and love for all life."

—Albert Schweitzer, who transitioned from human to Nature centric in 1915

Humans are the only animal who could detect an incoming planetesimal impact (or other threats) that would destroy all multicellular life on Earth and deflect it. We could evolve into beings that are to Earth as our brains are to our bodies. Or we will keep on keeping on and go extinct, taking perhaps all vertebrate life down the rabbit hole with us into an ecological blackhole.