1944

Christmas Story

Unabridged

By H.L. Mencken

Despite all the snorting against them in works of divinity, it has always been my experience that infidels—or freethinkers, as they usually prefer to call themselves—are a generally estimable class of men, with strong overtones of the benevolent and even of the sentimental. This was certainly true, for example, of Leopold Bortsch, Totsaufer [literally, dead-drinker, is a brewery's customers' man, One of his most important duties is to carry on in a wild and inconsolable manner at the funerals of saloonkeepers.] for the Scharnhorst Brewery, in Baltimore, forty-five years ago, whose story I have told, alas only piecemeal, in various previous communications to the press. If you want a bird's-eye view of his character, you can do no better than turn to the famous specifications for an ideal bishop in I Timothy III, 2-6. So far as I know, no bishop now in practice on earth meets those specifications precisely, and more than one whom I could mention falls short of them by miles, but Leopold qualified under at least eleven of the sixteen counts, and under some of them he really shone.

He was extremely liberal (at least with the brewery's money), he had only one wife (a natural blonde weighing a hundred and eighty-five pounds) and treated her with great humanity, he was (I quote the text) "no striker... not a brawler," and he was preëminently "vigilant, sober, of good behavior, given to hospitality, apt to teach." Not once in the days I knew and admired him, c. 1900, did he ever show anything remotely resembling a bellicose and rowdy spirit, not even against the primeval Prohibitionists of the age, the Lutheran pastors who so often plastered him from the pulpit, or the saloonkeepers who refused to lay in Scharnhorst beer. He was a sincere friend to the orphans, the aged, all blind and one-legged men, ruined girls, opium fiends, Chinamen, oyster dredgers, ex-convicts, the more respectable sort of colored people, and all the other oppressed and unfortunate classes of the time, and he slipped them, first and last, many a substantial piece of money.

Nor was he the only Baltimore infidel of those days who thus shamed the churchly. Indeed, the name of one of his buddies, Fred Ammermeyer, jumps into my memory at once. Fred and Leopold, I gathered, had serious dogmatic differences, for there are as many variations in doctrine between infidels as between Christians, but the essential benignity of both men kept them on amicable terms, and they often coöperated in good works. The only noticeable difference between them was that Fred usually tried to sneak a little propaganda into his operations— a dodge that the more scrupulous Leopold was careful to avoid. Thus, when a call went out for Bibles for the paupers lodged in Bayview, the Baltimore almshouse, Fred responded under an assumed name with a gross that had to be scrapped at once, for he had marked all the more antinomian passages with a red, indelible pencil— for example, Proverbs VII, 18-19; Luke XII, 19; I Timothy V, 23; and the account of David's dealing with Uriah in II Samuel XI.

Again, he once hired Charlie Metcalfe, a small-time candy manufacturer, to prepare a special pack of chocolate drops for orphans and ruined girls with a deceptive portrait of Admiral Dewey on the cover and a print of Bob Ingersoll's harangue over his brother's remains at the bottom of each box. Fred had this subversive exequium reprinted many times, and distributed at least two hundred and fifty thousand copies in Baltimore between 1895 and 1900. There were some Sunday-school scholars who received, by one device or another, at least a dozen. As for the clergy of the town, he sent each and every one of them a copy of Paine's "Age of Reason" three or four times a year— always disguised as a special-delivery or registered letter marked "Urgent." Finally, he employed seedy rabble rousers to mount soap boxes at downtown street corners on Saturday nights and there bombard the assembled loafers, peddlers, and cops with speeches which began seductively as excoriations of the Interests and then proceeded inch by inch to horrifying proofs that there was no hell.

But in the masterpiece of Fred Ammermeyer's benevolent career there was no such attempt at direct missionarying; indeed, his main idea when he conceived it was to hold up to scorn and contumely, by the force of mere contrast, the crude missionarying of his theological opponents. This idea seized him one evening when he dropped into the Central Police Station to pass the time of day with an old friend, a police lieutenant who was then the only known freethinker on the Baltimore force. Christmas was approaching and the lieutenant was in an unhappy and rebellious frame of mind—not because he objected to its orgies as such, or because he sought to deny Christians its beautiful consolations, but simply and solely because he always had the job of keeping order at the annual free dinner by the massed missions of the town to the derelicts of the waterfront, and that duty compelled him to listen politely to a long string of pious exhortations, many of them from persons he knew to be whited sepulchres.

"Why in hell," he observed impatiently, "do all them goddam hypocrites keep the poor bums waiting for two, three hours while they get off their goddam whimwham? Here is a hall full of men who ain't had nothing to speak of to eat for maybe three, four days, and yet they have to set there smelling the turkey and the coffee while ten, fifteen Sunday-school superintendents and W.C.T.U. [Women's Christian Temperance Union] sisters sing hymns to them and holler against booze. I tell you, Mr. Ammermeyer, it ain't human. More than once I have saw a whole row of them poor bums pass out in faints, and had to send them away in the wagon. And then, when the chow is circulated at last, and they begin fighting for the turkey bones, they ain't hardly got the stuff down before the superintendents and the sisters begin calling on them to stand up and confess whatever skullduggery they have done in the past, whether they really done it or not, with us cops standing all around. And every man Jack of them knows that if they don't lay it on plenty thick there won't be no encore of the giblets and stuffing, and two times out of three there ain't no encore anyhow, for them psalm singers are the stingiest outfit outside hell and never give a starving bum enough solid feed to last him until Christmas Monday. And not a damned drop to drink! Nothing but coffee—and without no milk! I tell you, Mr. Ammermeyer, it makes a man's blood boil."

Fred's duly boiled, and to immediate effect. By noon the next day he had rented the largest hall on the waterfront and sent word to the newspapers that arrangements for a Christmas party for bums to end all Christmas parties for bums were under way. His plan for it was extremely simple. The first obligation of hospitality, he announced somewhat prissily, was to find out precisely what one's guests wanted, and the second was to give it to them with a free and even reckless hand. As for what his proposed guests wanted, he had no shade of doubt, for he was a man of worldly experience and he had also, of course, the advice of his friend the lieutenant, a recognized expert in the psychology of the abandoned.

First and foremost, they wanted as much malt liquor as they would buy themselves if they had the means to buy it. Second, they wanted a dinner that went on in rhythmic waves, all day and all night, until the hungriest and hollowest bum was reduced to breathing with not more than one cylinder of one lung. Third, they wanted not a mere sufficiency but a riotous superfluity of the best five-cent cigars on sale on the Baltimore wharves. Fourth, they wanted continuous entertainment, both theatrical and musical, of a sort in consonance with their natural tastes and their station in life. Fifth and last, they wanted complete freedom from evangelical harassment of whatever sort, before, during, and after the secular ceremonies.

On this last point, Fred laid special stress, and every city editor in Baltimore had to hear him expound it in person. I was one of those city editors, and I well recall his great earnestness, amounting almost to moral indignation. It was an unendurable outrage, he argued, to invite a poor man to a free meal and then make him wait for it while he was battered with criticism of his ways, however well intended. And it was an even greater outrage to call upon him to stand up in public and confess to all the false steps of what may have been a long and much troubled life. Fred was determined, he said, to give a party that would be devoid of all the blemishes of the similar parties staged by the Salvation Army, the mission helpers, and other such nefarious outfits. If it cost him his last cent, he would give the bums of Baltimore massive and unforgettable proof that philanthropy was by no means a monopoly of gospel sharks—that its highest development, in truth, was to be found among freethinkers.

It might have cost him his last cent if he had gone it alone, for he was by no means a man of wealth, but his announcement had hardly got out before he was swamped with offers of help. Leopold Bortsch pledged twenty-five barrels of Scharnhorst beer and every other Totsaufer in Baltimore rushed up to match him. The Baltimore agents of the Pennsylvania two-fer factories fought for the privilege of contributing the cigars. The poultry dealers of Lexington, Fells Point, and Cross Street markets threw in barrel after barrel of dressed turkeys, some of them in very fair condition. The members of the boss bakers' association, not a few of them freethinkers themselves, promised all the bread, none more than two days old, that all the bums of the Chesapeake littoral could eat, and the public-relations counsel of the Celery Trust, the Cranberry Trust, the Sauerkraut Trust, and a dozen other such cartels and combinations leaped at the chance to serve.

If Fred had to fork up cash for any part of the chow, it must have been for the pepper and salt alone. . . . But the rent of the hall had to be paid, and not only paid but paid in advance, for the owner thereof was a Methodist deacon, and there were many other expenses of considerable size—for example, for the entertainment, the music, the waiters and bartenders, and the mistletoe and immortelles which decorated the ball. Fred, if he had desired, might have got the free services of whole herds of amateur musicians and elocutionists, but he swept them aside disdainfully, for he was determined to give his guests a strictly professional show. . . . He got, of course, some contributions in cash from rich freethinkers, but when the smoke cleared away at last and he totted up his books, he found that the party had set him back more than a hundred and seventy-five dollars.

Admission to it was by invitation only, and the guests were selected with a critical and bilious eye by the police lieutenant. No bum who had ever been known to do any honest work—even such light work as sweeping out a saloon—was on the list. By Fred's express and oft-repeated command it was made up wholly of men completely lost to human decency, in whose favor nothing whatsoever could be said. The doors opened at 11 a.m. of Christmas Day, and the first canto of the dinner began instantly. There were none of the usual preliminaries—no opening prayer, no singing of a hymn, no remarks by Fred himself, not even a fanfare by the band. The bums simply shuffled and shoved their way to the tables and simultaneously the waiters and sommeliers poured in with the chow and the malt. For half an hour no sound was heard save the rattle of crockery, the chomp-chomp of mastication, and the grateful grunts and "Oh, boy!"s of the assembled underprivileged.

Then the cigars were passed round (not one but half a dozen to every man), the band cut loose with the tonic chord of G major, and the burlesque company plunged into Act I, Sc. 1 of "Krausmeyer's Alley." There were in those days, as old-timers will recall, no less than five standard versions of this classic, ranging in refinement all the way from one so tony that it might have been put on at the Union Theological Seminary down to one so rowdy that it was fit only for audiences of policemen, bums, newspaper reporters, and medical students. This last was called the Cincinnati version, because Cincinnati was then the only great American city whose mores tolerated it. Fred gave instructions that it was to be played à outrance and con fuoco, with no salvo of slapsticks, however brutal, omitted, and no double-entendre, however daring. Let the boys have it, he instructed the chief comedian, Larry Snodgrass, straight in the eye and direct from the wood. They were poor men and full of sorrow, and he wanted to give them, on at least one red-letter day, a horse-doctor's dose of the kind of humor they really liked.

In that remote era the girls of the company could add but little to the exhilarating grossness of the performance, for the strip tease was not yet invented and even the shimmy was still only nascent, but they did the best they could with the muscle dancing launched by Little Egypt at the Chicago World's Fair, and that best was not to be sneezed at, for they were all in hearty sympathy with Fred's agenda, and furthermore, they cherished the usual hope of stage folk that Charles Frohman or Abe Erlanger might be in the audience. Fred had demanded that they all appear in red tights, but there were not enough red tights in hand to outfit more than half of them, so Larry Snodgrass conceived the bold idea of sending on the rest with bare legs. It was a revolutionary indelicacy, and for a startled moment or two the police lieutenant wondered whether he was not bound by his Hippocratic oath to raid the show, but when be saw the whole audience leap up and break into cheers, his dubieties vanished, and five minutes later he was roaring himself when Larry and the other comedians began paddling the girls' cabooses with slapsticks.

I have seen many a magnificent performance of "Krausmeyer's Alley" in my time, including a Byzantine version called "Krausmeyer's Dispensary," staged by the students at the Johns Hopkins Medical School, but never have I seen a better one. Larry and his colleagues simply gave their all. Wherever, on ordinary occasions, there would have been a laugh, they evoked a roar, and where there would have been roars they produced something akin to asphyxia and apoplexy. Even the members of the musicians' union were forced more than once to lay down their fiddles and cornets and bust into laughter. In fact, they enjoyed the show so vastly that when the comedians retired for breath and the girls came out to sing "Sweet Rosie O'Grady" or "I've Been Workin' on the Railroad," the accompaniment was full of all the outlaw glissandi and sforzandi that we now associate with jazz.

The show continued at high tempo until 2 p.m., when Fred shut it down to give his guests a chance to eat the second canto of their dinner. It was a duplicate of the first in every detail, with second and third helpings of turkey, sauerkraut, mashed potatoes, and celery for everyone who called for them, and a pitcher of beer in front of each guest. The boys ground away at it for an hour, and then lit fresh cigars and leaned back comfortably for the second part of the show. It was still basically "Krausmeyer's Alley," but it was a "Krausmeyer's Alley" adorned and bedizened with reminiscences of every other burlesque-show curtain raiser and afterpiece in the repertory. It went on and on for four solid hours, with Larry and his pals bending themselves to their utmost exertions, and the girls shaking their legs in almost frantic abandon. At the end of an hour the members of the musicians' union demanded a cut-in on the beer and got it, and immediately afterward the sommeliers began passing pitchers to the performers on the stage. Meanwhile, the pitchers on the tables of the guests were kept replenished, cigars were passed round at short intervals, and the waiters came in with pretzels, potato chips, celery, radishes, and chipped beef to stay the stomachs of those accustomed to the free-lunch way of life.

At 7 p.m. precisely, Fred gave the signal for a hiatus in the entertainment, and the waiters rushed in with the third canto of the dinner. The supply of roast turkey, though it had been enormous, was beginning to show signs of wear by this time, but Fred had in reserve twenty hams and forty pork shoulders, the contribution of George Wienefeldter, president of the Weinefeldter Bros. & Schmidt Sanitary Packing Co., Inc. Also, he had a mine of reserve sauerkraut hidden down under the stage, and soon it was in free and copious circulation and the guests were taking heroic hacks at it. This time they finished in three-quarters of an hour, but Fred filled the time until 8 p.m. by ordering a seventh inning stretch and by having the police lieutenant go to the stage and assure all hands that any bona-fide participant found on the streets, at the conclusion of the exercises, with his transmission jammed would not be clubbed and jugged, as was the Baltimore custom at the time, but returned to the hall to sleep it off on the floor. This announcement made a favorable impression, and the brethren settled down for the resumption of the show in a very pleasant mood. Larry and his associates were pretty well fagged out by now, for the sort of acting demanded by the burlesque profession is very fatiguing, but you'd never have guessed it by watching them work.

At ten the show stopped again, and there began what Fred described as a Bierabend, that is, a beer evening. Extra pitchers were put on every table, more cigars were banded about, and the waiters spread a substantial lunch of rye bread, rat-trap cheese, ham, bologna, potato salad, liver pudding, and Blutwurst. Fred announced from the stage that the performers needed a rest and would not be called upon again until twelve o'clock, when a midnight show would begin, but that in the interval any guest or guests with a tendency to song might step up and show his or their stuff. No less than a dozen volunteers at once went forward but Fred had the happy thought of beginning with a quartet, and so all save the first four were asked to wait. The four laid their heads together, the band played the vamp of "Sweet Adeline," and they were off. It was not such singing as one hears from the Harvard Glee Club or the Bach Choir at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, but it was at least as good as the barbershop stuff that hillbillies now emit over the radio. The other guests applauded politely, and the quartet, operating briskly under malt and hop power, proceeded to "Don't You Hear Dem Bells?" and "Aunt Dinah's Quilting Party." Then the four singers had a nose-to-nose palaver and the first tenor proceeded somewhat shakily to a conference with Otto Strauss, the leader of the orchestra.

From where I sat, at the back of the hall, beside Fred, I could see Otto shake his head, but the tenor persisted in whatever he was saying, and after a moment Otto shrugged resignedly and the members of the quartet again took their stances. Fred leaned forward eagerly, curious to hear what their next selection would be. He found out at once. It was "Are You Ready for the Judgment Day?," the prime favorite of the period in all the sailors' bethels, helping-up missions, Salvation Army bum traps, and other such joints along the waterfront. Fred's horror and amazement and sense of insult were so vast that he was completely speechless, and all I heard out of him while the singing went on was a series of sepulchral groans. The man was plainly suffering cruelly, but what could I do? What, indeed, could anyone do? For the quartet had barely got half way through the first stanza of the composition before the whole audience joined in. And it joined in with even heartier enthusiasm when the boys on the stage proceeded to "Showers of Blessings," the No. 2, favorite of all seasoned mission stiffs, and then to "Throw Out the Lifeline," and then to "Where Shall We Spend Eternity?," and then to "Wash Me, and I Shall Be Whiter Than Snow."

Half way along in this orgy of hymnody, the police lieutenant took Fred by the arm and led him out into the cold, stinging, corpse-reviving air of a Baltimore winter night. The bums, at this stage, were beating time on the tables with their beer glasses and tears were trickling down their noses. Otto and his band knew none of the hymns, so their accompaniment became sketchier and sketchier, and presently they shut down altogether. By this time the members of the quartet began to be winded, and soon there was a halt. In the ensuing silence there arose a quavering, boozy, sclerotic voice from the floor. "Friends," it began, "I just want to tell you what these good people have done for me—how their prayers have saved a sinner who seemed past all redemption. Friends, I had a good mother, and I was brought up under the influence of the Word. But in my young manhood my sainted mother was called to heaven, my poor father took to rum and opium, and I was led by the devil into the hands of wicked men—yes, and wicked women, too. Oh, what a shameful story I have to tell! It would shock you to hear it, even if I told you only half of it. I let myself be. . ."

I waited for no more, but slunk into the night. Fred and the police lieutenant had both vanished, and I didn't see Fred again for a week. But the next day I encountered the lieutenant on the street, and he hailed me sadly. "Well," be said, "what could you expect from them bums? It was the force of habit, that's what it was. They have been eating mission handouts so long they can't help it. Whenever they smell coffee, they begin to confess. Think of all that good food wasted! And all that beer! And all them cigars!"

I read online versions, some obviously abridged by Christians. I picked one that appeared unabridged. Then I bought the book. I added the missing offending bits which are underscored in indelible red pencil. From the dust jacket:

H.L. Mencken, with an author's tenderness for his offspring, describes this little book as "a Christmas story to surpass, transcend and put an end to all other Christmas stories." He says that it is full of "psychology, sociology, theology (both moral and dogmatic), ethics, aesthetics, economics, penology, psychiatry and sex appeal." "It is aimed, " he goes on, "at infidels, and yet it should delight and ravish the pious. It is as immoral as a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States, and yet it packs one of the damnedest morals ever recorded in the literature of the Western World." All this is crowded into 32 pages, with room for the gaudy pictures by Bill Crawford. It is the author's shortest book. His last ran to 790 pages.

Original price: $1.95

H.L. Mencken's "great fable" was printed as Stare Decisis in The New Yorker (December 30, 1944). Two years later it came out as a small book titled Christmas Story. As Martin Gardner notes, "On its top metaphorical level Mencken's banquet is a symbol of today's Western world. Fred Ammermeyer is modern science and technology, hooked on alcohol, obsessed by porn, and unable to forget our Christian past."

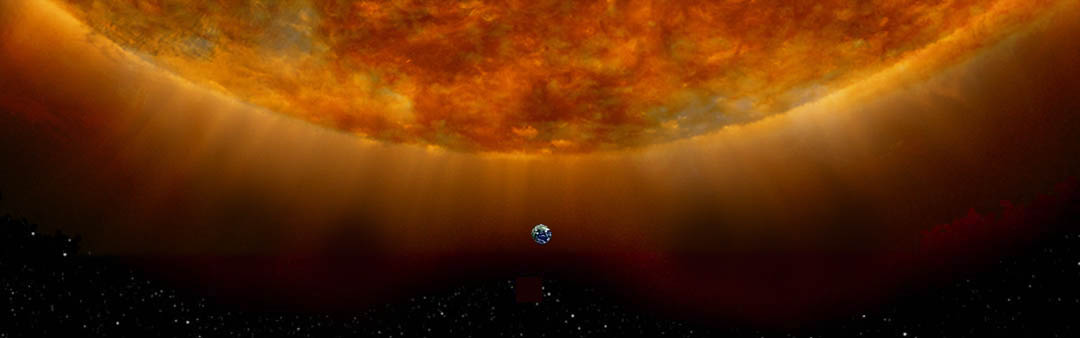

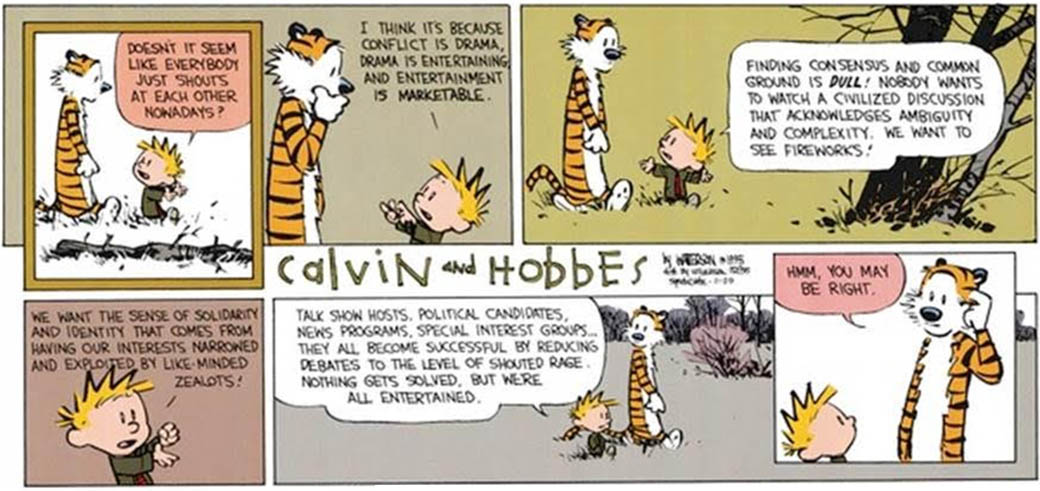

Who are the bums? We are, all who live within the industrial consumer society, all who would rather believe than know. Some bums have more than others, some way more, some work hard to consume more. Our bums' growth party has lasted two hundred years. It went into overdrive/excess with the Great Acceleration about 1950 that we of the overdeveloped world, we self-taught five-year-olds with machetes, are living unsustainably in the final hours of. It has been a party to end all parties made possible by Earth's vat of stored energy and resources hundreds of millions of years in the storing.

Who are the freethinkers? The providers of the banquet, of the science and fossil-fueled technology that for a time provided the stuff—the alcohol and drugs, the excess of food and entertainment unto jadedness, the distractions, the collective obesity unto collapse. But we're all entertained. We still have bread and circus. When growth falters we'll demand salvation and solutions. Think of all the planetary commons we bums have wasted!

And to give the devil his due:

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/H._L._Mencken#Quotes