.

SUNDAY, OCT 20, 2019

Dark Mountain

A Manifesto

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: HUMANITIES, UNCIVILISATION, FROM THE WIRES, THINKING ABOUT DESCENT

Abstract: I've come across several references to Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto of 2009, but a copy I could quote from by copy/paste wasn't found initially, so I ending up typing a bit of the manifesto to share. At the same time I was reading Dark Mountain, I was reading Derrick Jensen's manifesto-like offerings. From the Dark Mountain, things look slightly different to me, but why quibble? Nothing facepalming to see here folks. Beam me up, Paul.

COOS BAY (A-P) — To boil it down: things fall apart. The narratives of the merely eloquent no longer serve. The myth of illimitable progress becomes unbelieved in. Wordsmiths become unemployed. No one has time to listen. The never-ending story ends. After dissolution, new stories arise. Some start to form during the endgame. Eventually we will tell better stories (or go extinct).

COOS BAY (A-P) — To boil it down: things fall apart. The narratives of the merely eloquent no longer serve. The myth of illimitable progress becomes unbelieved in. Wordsmiths become unemployed. No one has time to listen. The never-ending story ends. After dissolution, new stories arise. Some start to form during the endgame. Eventually we will tell better stories (or go extinct).

To end the pattern, to end the mere storytelling, the story of no story comes about. The paradigm of no true paradigms comes upon our teachable minds (when the moment comes), which is itself a paradigm. Darkness gives way to light. Stories are told, but no one believes a word of them. Models are made but they are not the system modeled. The what-is becomes apparent when our stories about its Suchness falter before the Not-two. We call concepts real (or true) only because of our ignorance.

There is one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that no paradigm [belief system, ideology] is 'true,' that everyone, including those that sweetly sing your own worldview, has a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension. It is to 'get' at a gut-level the paradigm that there are paradigms [that are not 'true'], and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realization as devastatingly funny. It is to let go into not-knowing, into what the Buddhists call enlightenment.

It is in this space of mastery over paradigms that humans throw off addictions [their purpose-driven Calhoun-rat consumer life], live in constant joy [when not dealing with life debilitating situations], bring down empires [so what are you waiting for?], get locked up, or burned at the stake or crucified or shot, and have impacts that last for millennia.

There is so much that could be said to qualify this list [see chapter six] of places to intervene in a system. It is a tentative list and its order is slithery. There are exceptions to every item that can move it up or down the order of leverage. Having had the list percolating in my subconscious for years has not transformed me into a Superwoman. The higher the leverage point, the more the system will resist changing it—that's why societies often rub out truly enlightened beings.

Magical leverage points are not easily accessible, even if we know where they are and which direction to push on them. There are no cheap tickets to mastery. You have to work hard at it, whether that means rigorously analyzing a system or rigorously casting off your own paradigms and throwing yourself into the humility of Not Knowing. In the end, it seems that mastery has less to do with pushing leverage points than it does with strategically, profoundly, madly, letting go and dancing with the system.

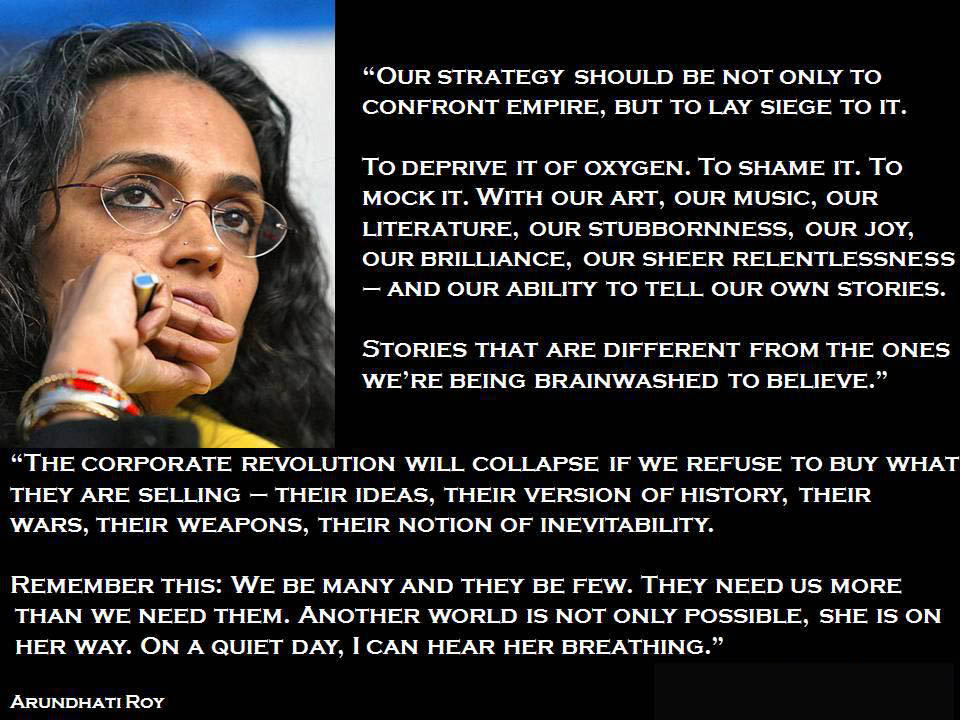

Alternative to uncivilization, transhumanism, or any non-viable civilization (e.g. modern techno-industrial society), would be a civilization (complex society) based on listening to Nature, who has all the answers, instead of listening to the mere eloquence of primate prattle. A viable civilization could be based on unbelief, on not believing in belief (e.g. humanism, human centrism). To persist as the millennia pass, do what Nature selects for. Humans don't get a vote. The stories told by the storytelling animal are distractions. The endeavor to tell the most likely stories about the what-is, to iterate towards 'truth', is adaptive, or might be if we tried it on a civilizational scale. The despair of the storytelling intelligentsia shall pass away with their belief in belief. An ecolate civilization is not only possible, but on a quiet day I can here her breathing.

From Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto

by Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine

The end of the human race will be that it will eventually die of civilisation.

— Ralph Waldo EmersonHuman civilisation is an intensely fragile construction. It is built on little more than belief: belief in the rightness of its values; belief in the strength of its system of law and order; belief in its currency; above all, perhaps, belief in its future.

Once that belief begins to crumble, the collapse of a civilisation may become unstoppable. That civilisations fall, sooner or later, is as much a law of history as gravity is a law of physics. What remains after the fall is a wild mixture of cultural debris, confused and angry people whose certainties have betrayed them, and those forces which were always there, deeper than the foundations of the city walls: the desire to survive and the desire for meaning.

This time, the crumbling empire is the unassailable global economy, and the brave new world of consumer democracy being forged worldwide in its name. Upon the indestructibility of this edifice we have pinned the hopes of this latest phase of our civilisation. Now, its failure and fallibility exposed, the world’s elites are scrabbling frantically to buoy up an economic machine which, for decades, they told us needed little restraint, for restraint would be its undoing. Uncountable sums of money are being funnelled upwards in order to prevent an uncontrolled explosion. The machine is stuttering and the engineers are in panic. They are wondering if perhaps they do not understand it as well as they imagined. They are wondering whether they are controlling it at all or whether, perhaps, it is controlling them.

We are the first generations to grow up surrounded by evidence that our attempt to separate ourselves from ‘nature’ has been a grim failure, proof not of our genius but our hubris... Of all humanity’s delusions of difference, of its separation from and superiority to the living world which surrounds it, one distinction holds up better than most: we may well be the first species capable of effectively eliminating life on Earth... We are the first generations born into a new and unprecedented age – the age of ecocide.

Today, humanity is up to its neck in denial about what it has built, what it has become—and what it is in for. Ecological and economic collapse unfold before us and, if we acknowledge them at all, we act as if this were a temporary problem, a technical glitch. Centuries of hubris block our ears like wax plugs; we cannot hear the message which reality is screaming at us. For all our doubts and discontents, we are still wired to an idea of history in which the future will be an upgraded version of the present. The assumption remains that things must continue in their current direction: the sense of crisis only smudges the meaning of that 'must'. No longer a natural inevitability, it becomes an urgent necessity: we must find a way to go on having supermarkets and superhighways. We cannot contemplate the alternative...

There are the serious stories told by economists, politicians, geneticists and corporate leaders. These are not presented as stories at all, but as direct accounts of how the world is. Choose between competing versions, then fight with those who chose differently. The ensuing conflicts play out on early morning radio, in afternoon debates and late night television pundit wars [and more recently in internet echo chambers]. And yet, for all the noise, what is striking is how much the opposing sides agree on: all their stories are only variants of the larger story of human centrality, of our ever-expanding control over 'nature', our right to perpetual economic growth, our ability to transcend all limits.

The Eight Principles of Uncivilisation

'We must unhumanise our views a little, and become confident

As the rock and ocean that we were made from.'

- We live in a time of social, economic and ecological unraveling. All around us are signs that our whole way of living is already passing into history. We will face this reality honestly and learn how to live with it.

- We reject the faith which holds that the converging crises of our times can be reduced to a set of 'problems' in need of technological or political 'solutions'.

- We believe that the roots of these crises lie in the stories we have been telling ourselves. We intend to challenge the stories which underpin our civilisation: the myth of progress, the myth of human centrality, and the myth of our separation from 'nature'. These myths are more dangerous for the fact that we have forgotten they are myths.

- We will reassert the role of story-telling as more than mere entertainment. It is through stories that we weave reality.

- Humans are not the point and purpose of the planet. Our art will begin with the attempt to step outside the human bubble. By careful attention, we will reengage with the non-human world.

- We will celebrate writing and art which is grounded in a sense of place and of time. Our literature has been dominated for too long by those who inhabit the cosmopolitan citadels.

- We will not lose ourselves in the elaboration of theories or ideologies. Our words will be elemental. We write with dirt under our fingernails.

- The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop. Together, we will find the hope beyond hope, the paths which lead to the unknown world ahead of us.

Science is storytelling, the endeavor to tell the most likely stories. The proposed Federation and its naturocracy alternative to BAU/GND, involves science as foundational to our storytelling, but it is not the only or even the best voice. We must listen to Nature as Voice on High, who speaks to the poet and scientist in a varied language. Science may not need all of our stories, but we need to tell better stories. The word for the 21st century is consilience. But facepalming narratives involving certitudes or deeply held beliefs need to end up inside dusty books. The heads of some storytellers need to end up on metaphorical pikes (e.g. all political and religious ideologues) so fewer real heads need to. Noting that neoclassical economics is pretend science and removing it from about 22,000 colleges and universities would be a good start.

And as imitation is the sincerist form of flatery, I featured my wife as Aluna in a twicetold tale: