TUESDAY, JAN 24, 2023: NOTE TO FILE

Module 3-2

The Rationale For Regenerative Agriculture

2.1. Species Diversity and Ecosystems Functions

The IPBES Global Assessment Report published in May 2019 for the UN Convention on Biological Diversity puts habitat loss as the number one direct driver of the loss of biodiversity and species extinctions with agriculture and urbanisation [over half of humans now live in urban areas and all others consume industrially produced, transported, and processed foods, i.e. human population is the other major driver without which there would be no agriculture] mentioned as the primary drivers. The report specifically states that climate change is not a direct driver of habitat loss but exacerbates existing drivers [i.e. climate change is a distraction, a symptom of humanity's ecological and civilizational overshoot, especially over the last 300 years]. To recap, in Module 2, we also looked at the disruption of the hydrological cycle and saw that ecosystems were dehydrated by loss of vegetation and urbanisation leading to desertification and collapse. In this module, we will look at the many ways that we can regenerate ecosystems and restore the carbon and hydrological cycles through a transition to agro-ecological practices appropriate to our own bioregion [able to sustainably support perhaps one tenth of current populations within bioregions]. It comes at a moment in time when the IPCC has also published the Climate Change and Land report (August 2019) with suggestions for using reforestation and regenerative agriculture as Negative Emissions Technologies to draw down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as part of a Net Zero Emissions strategy to tackle climate change. We will also look at the potential for carbon sequestration among the various agricultural methods proposed.

The ‘conventional’ agricultural practices that were implemented during the so-called Green Revolution in the 1960s have produced increased yields of grains, but at a terrible cost to the land and to farmers. In the global North, governmental and EU systems of subsidies for farmers have obliged them to remove hedgerows, drain wetlands and log woodlands to qualify for payments and the dominance of supermarket chains and food processing transnationals in the retail sector have forced down the price they are paid for their produce. Farmers are also squeezed through debts to banks and agri-businesses: modern farm equipment comes with a price and the cost of seed, artificial fertilisers and chemicals from the big corporations keep farmers on the treadmill. As small farmers go out of business or retire, their land is taken over by corporate agribusinesses, and those farmers that remain are locked into the subsidy system, with degraded land and massive loans that render change almost impossible. This is why they need help and support to make the transition from consumers like ourselves and from our governments and institutions.

‘Conventional’ agriculture, also referred to as ‘specialised industrial agriculture’ (SIA) requires massive inputs of chemicals in the form of fertilisers, pesticides, herbicides and fungicides which has a profound effect on the environment. Recent tests carried out in Germany show that glyphosate, the most commonly used herbicide, can be found in rainwater, tap water, urban dust and in human urine. Runoff from compacted fields also carries nitrogen and phosphates poisoning rivers and lakes. The nitrogen feeds algal blooms which cut off oxygen from other species causing ‘dead zones’ in the oceans where marine life cannot survive.

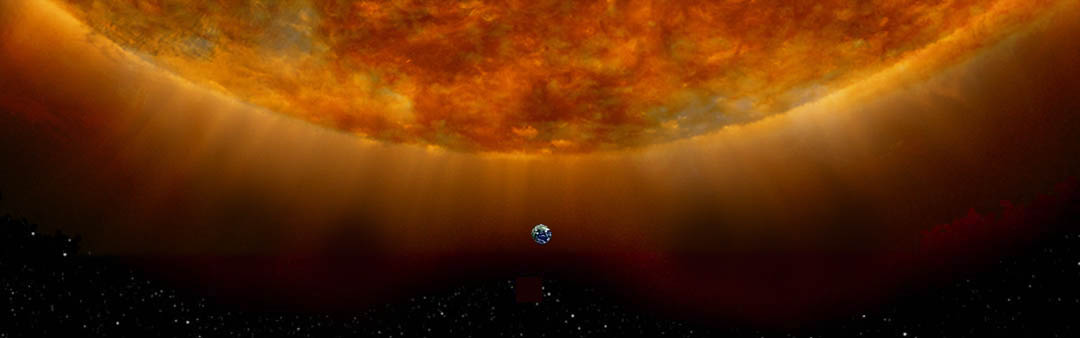

‘Conventional’ agriculture removes habitat for wildlife. When this happens, we lose the ecosystems functions that maintain a healthy environment and functional cycles of the biosphere, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Global trade in foodstuffs is equally a driver of degradation and carbon emissions. It is largely unnecessary and is a particular driver of socio-economic and environmental injustice in the global South. The UN Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Professor Olivier de Schutter, has called repeatedly for an end to the global trade in food and a transition to food sovereignty facilitated by small-scale agro-ecology. Naturally, a transition to regenerative agriculture and sustainable food production and consumption is essential to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Eliminating poverty, hunger and inequality are evidently achievable through a transition to local, regenerative agricultural practices, but likewise education and urbanisation can be positively impacted by a transition to locally grown food, and the environmental goals cannot be achieved at all without a transition. Agriculture is the key to a regenerative future. [Eliminating all forms of agriculture from 80% of arable lands is key to leaving room for Nature.]

Agro-ecology is used as an umbrella term to describe a range of practices or it is the term that designates a particular practice in some countries, particularly in the global south. It implies growing food as a form of edible ecosystem in which farmers mimic nature for diversity, fertility, pollination and (biological or integrated) pest control. As natural ecosystems are polycultures consisting mostly of perennials with high levels of biodiversity below and above ground and a ‘sponge’ of soil organic carbon that maintains the water cycle, it makes sense that the proposed methods include these features. We find agro-forestry and silvopasture combining productive trees with crops and animals are the most productive in some bioregions where open-canopy woodlands with meadows are the norm, and they also sequester high levels of CO2. No-till polyculture cropping in rotation with animals is also being researched extensively with groundcover crops that build soil carbon and maintain the soil microbiome. When savannah or prairie is the predominant biome, stamped into the landscape by massive herds of bison or other ungulates (hooved animals), grazing cattle can be used (see mob grazing and holistic planned management) to restore and rehydrate grasslands. Ungulates can also be used to ‘wild’ degraded arable land restoring it to biodiverse ecosystems. Permaculture, which perfectly matches the biome to the methods through detailed and conscious design, straddles all of these and is admirably suited to regeneration of entire watersheds. Urban agriculture is already showing great promise as means to provide inhabitants with food security while enhancing urban ecology, greening and cooling cityscapes. [Agro-forestry, silvopasture, garden plots and pasture on 20% at most within any watershed area without fossil fuel inputs would leave room for Nature and support perhaps 7 to 35 million humans depending on the level of per capita consumption.]

No monoculture of annual crops or animal husbandry that relies on inputs (chemical or organic) from outside the ecosystem will ever be sustainable [correct, but add that maybe one tenth the current population could be supported IF NO ROOM IS LEFT FOR NATURE ON LAND OR SEA]; it is more like mining the soil than farming.

Module 3, lesson 3