SATURDAY, JULY 21, 2018: NOTE TO FILE

Jeremy Lent on China

Paraphrased with comments

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: LAOZI, FROM THE WIRES, LI, QI, CONFUCIUS, SYSTEMS SCIENCE

Abstract: Lent is not a scientist type, though he is among the few who has taken an interest in systems science. I reread this 2017 book that included much about China I wanted to share with some Chinese scientists, so I took notes. The current empire didn't begin in China, but it may end with the descent of China. If all is not lost, preserving information and a remnant of functional society may occur in China among those with foresight intelligence.

TUCSON (A-P) —This preview/review of Jeremy Lent's The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning will focus on China. In Chapter 6, Lent notes that only one early complex society remained intact through the past thirty-five hundred years, namely China which continues to bequeath patterns of thought those in modern times need to seriously consider. Chinese culture has maintained enough cohesion through the millennia that it can rightly claim to have the oldest continuous civilization.

Elsewhere the different branches of the original PIE (Proto-Indo-European) culture spread forth with their livestock to impose their views of the fundamental nature of the universe, their beliefs in "truth, order, and righteousness" (e.g. Vedic, Greek, and Zoroastrian cosmologies) which can be summed up as "Might is right," that conquest is proof of superiority.

So how did a group of illiterate nomads leave such a profound imprint on the thought patterns of billions of us today, including those who serve the growth hegemon in China today? How did steppe pastoralists impose their language on so much of Europe west of their steppes and their culture to the east (e.g. Mongols)? It took more than guns, germs, and steel. Warriors on horseback were the ultimate terror weapon, as Pizarro demonstrated in more recent times. Indeed, even without guns, germs, and steel, PIE horsemen (not women) pushed ahead to enable waves of migrations (Kurgan expansion) to subsume hunter-gatherers and farmers living in egalitarian, matriarchal societies, telling metaphorical stories of the mother goddess. PIE invaders took fifteen hundred years to impose their patriarchal values and aggression over a vast area, Eurasia and India, in ways that proved to be as devastating (Late Bronze Age collapse) as they are proving to be and likely will prove to be in the twenty-first century (but this time around on a planetary scale).

The PIE cowboys, in one of the early waves who prospered on the plains of northern Iran, formed complex societies based on energy derived from grazing animals. They were soon joined by PIE nomadic cattle rustlers, and as the only good rustler is a dead rustler, Zoroaster (Zarathustra) created a religious control system to explain the state of unremitting conflict, given that the settled PIE cattle breeders could not exterminate the more nomadic horsebacked PIE raiders. Zoroastrianism spread, and persisted as a major force until displaced by a more virulent force in the seventh century CE (Islam) that itself was derived from the nearly as virulent Judeo-Christian hegemon that derived it's big ideas from Zoroaster (while enslaved in Babylon). Zoroaster was every inch a PIE enthusiast for going forth (conquest) and multiplying (subsuming the conquered linguistically and culturally). For a time culturally PIE-like Mongols on horseback even invaded and conquered China, but were soon subsumed by superior Chinese ways, failing to impose their language or culture upon the bureaucrats or people of China. The PIE Aryans had better luck in India. PIE descendants encountered no significant opposition in the Americas, Africa, Australia, Polynesia, and elsewhere.

China did lose the Opium Wars, prior to which (1820) China had the largest economy in the world, but in the twentieth century, ideologue political leaders used PIE inspired political ideology to unite the Chinese people, including those who didn't want to be, in a PIE cultural revolution, and by the late twentieth century the global PIE nation-state 'building' (to commit empire) had subsumed China by turning the Chinese intelligentsia and their followers into enthusiastic Anthropocene consumers and producers deliriously happy to grow their economy at 7% to 10% (for a time) by consuming half the coal being consumed on the planet. In the early twenty-first century they were giving their children PIE descendant names, and even celebrating 'sustainable development' along with all the other PIE-cultured growthers (empire-builders) on the planet (for a time).

The original PIE idea of rta was of a dualistic, otherworldly, transcendent force of the universe. The Greek expression of rta was to make reason divine, as was the Mind that engaged in it, as distinct from the beastly brain/body as worthless containers. The Aryan expression of rta took the form of a transcendent pantheism. The Greek philosophers used their new tools of reason and logic to understand the world, and the gods themselves were among the first casualties. In India, the opposite was the case as the gods of the indigenous became inexorably linked to the transcendent Self (atman) and Brahman. By linking divinity to reason [done by Plato, not 'the Greeks'], something only humans were thought to be capable of, 'the Greeks' [those who followed Plato] viewed all other creatures as lacking in divinity. This dichotomy between humans and the rest of the natural world [thank you Plato] became a central theme of Western thought [note: Plato's complete works survived only because Neoplatonist Christian apologists found them useful, while 90 percent of Greek literature/philosophy was burned/destroyed or not valued and lost]. In the Vedic tradition reason was merely a tool used in the service of 'true' divinity (atman/Brahman identity). In science, reason is a tool useful for finding things out, but nothing divine or transcendent about it.

The alternative understanding of the universe, a non-dualistic, this-worldly view, arose 3,500 years ago in a region untouched by Indo-European 'migration' [aka conquest]. During the Warring States period two thoughtful gentlemen were walking in a garden. One turned and asked the other:

"This thing called the Tao [Nature], where does it exist?"

"There is no place it doesn't exist," came the answer.

"Come now," said Tung-kuo, "you must be more specific!"

"It's in the ant."

"As low a thing as that?"

"It is in the grass."

"But that's lower still!"

"It is in your piss and shit."

Stunned, Master Tung-kuo made no reply.

The gentleman answering the questions was Zhuangzi, whom many scholars [who mostly lived in China over the past 2,300 years] consider the most brilliant philosopher known to history, who considered himself a humble student of Laozi ('Tao everlasting is the nameless uncarved wood...'), author of the Tao Te Ching, the views of whom are foundationally inconsillient with PIE dualism [i.e. both could be wrong, but both can't be 'right']. From a sciency point of view, urine is a valuable liquid fertilizer (11-1-2.5) and human excrement composts naturally (or with a little help) to enrich soils if we don't use our drinking water to flush it to 'somewhere else'.

The Tao doesn't exist as an abstract Idea as Plato would have insisted, nor is it ABOVE material things or hidden deep WITHIN all things as the Indian wordsmiths conceived atman. Instead, the Tao is the 'uncarved wood' [among other things that may or may not be in front of your face] as reality, the what-is apart from which not a thing is. Science... ditto. The Chinese model of the universe never posited a transcendent dimension of eternal meaning. In the Chinese universe there was no eternal soul; no pure, abstract Mind creating and directing the universe. Instead, the Chinese found the most profound source of meaning within the everyday, material dimension of life.

Traditional Chinese cosmology is based on the root metaphor of the world as one gigantic organism [biosphere as self-organizing complex system], a more explanatory model of the natural world than the mechanistic pre-systems science models. In ancient Greece, where reason was deified, the primary objective of a philosopher was the cultivation of the intellect. In ancient India, the goal of Yoga was to shed the illusory layers of consciousness until a person could arrive at self-realization. In ancient China, where cosmic harmony was seen as the way of the universe, the ultimate intention of the sage was to learn from Nature and live according to Nature's harmonious principles [li], the ones that work as determined by the nature of things.

For the Chinese, there was no separate, abstract human soul trying to escape the pollution of the changeable world. Rather, each human being was seen as a natural system [subsystem] embedded dynamically within the network of the cosmos [system], intertwined between heaven and earth. Humanity did not exist separately from Nature but was intrinsically connected to it [we are the environment]. There is no sense in trying to conquer Nature; rather, humans should harmonize with it. Harmony between humans did not imply agreement. You could disagree with someone while still maintaining harmony [as in science any disagreement means not enough data—evidence, resulting in a harmonious, cooperative effort to learn more, to listen better to Nature (or notice that bias or self interest is getting in the way of understanding, of doing science)].

The ancient Greeks [Platonists] viewed the human body as a tomb in which the soul is imprisoned. The Upanishads gave the promise of immortality to those who renounced the illusory world of maya. The Taoists, on the other hand, put their attention into how to live in this world rather than prepare for an imagined one. For the Greeks, reason was divine, and the human ability to create abstractions was the pathway to divinity. For the Indians, the 'discriminating intellect' was the charioteer driving atman to enlightenment, harnessing the wild horses of the senses. For the Taoists, the discriminating, reasoning faculty was the source of yu-wei [purpose-driven action calculated to serve self interest], the raise of complex society, and the loss of the harmony available to humans through effortless action [wu-wei, action that goes with the flow, secondary to listening to Nature, as distinct from going against the grain of things, which implies understanding Nature as system, the nature of things as a complex system of subsystems of which 'you' as 'individual' are inseparably part of].

Confucius said, "Man is able to enlarge the Tao, it is not that the Tao enlarges man." This is the key point of difference between Confucianism and Taoism. While the Taoist practice of wu-wei encourages a person to shed the accouterments of civilization [conditioning] and become like the uncarved piece of wood [authentic], for Confucians, there are elements of civilization that enable humanity to "enlarge the Tao," essentially improving on Nature [i.e. to become solemn pretenders, to practice human exceptionalism, human supremacy, humancentric dominionism achievable, per Confucius, via ritual observances (li—detailed prescriptions for behavior)]. Believe in li, practice it, do as you're told and maybe you'll eventually become an enlightened sage... (or not). You better believe it. Rather than shedding layers of 'civilization' [conditioning], the Confucian sought to integrate them into his 'true' nature [as true believer]. According to one interpreter, "The human being is not only heir to and transmitter of tao, but is, in fact, its ultimate creator. Thus... the tao emerges out of human activity... is ultimately of human origin." And, no, it wasn't a Taoist sage who opined such a view of man and Nature (Tao). The Tao Te Ching barely conceals its distaste for the very li that Confucius saw as sacrosanct, and Zhuangzi did not conceal his contempt for Confucian true believers or the 'verities' they followed. Li, as belief, comes into existence only after te is lost.

In the West today, the split between the Romantic and Enlightenment values followed the split between emotion and reason inherited ultimately from Platonic dualism, and, to this day, most discourse, our endless narratives, are crouched in these dualistic terms. Thank you, Plato. The Chinese tradition took a different, a more illuminating path as both Taoists and Confucians agreed that harmonizing with Nature was their ultimate objective. Whether Taoists or Confucians offered the better view was debated. In the Song dynasty some Neo-Confucians sought to synthesize the seeming twain with yet another more coherent view offered by the latecomer Buddha.

Descartes's foundational statement of Western philosophy, "I think, therefore I am," becomes, in Chinese, "Thinking, therefore being." The subject-verb-object pattern, man bites dog, is Indo-European. "The man bites the dog" is Greco-Indo-European, as Plato based his entire philosophy of Forms upon "the" and marvelous indeed is the concept-mongering magic the definite article allows Western wordsmiths to practice as a sorcerer practices spells. It allows the merely eloquent, but often celebrated, obfuscators to speak of THE Truth, or of the One True God and myriad other verities, meaningless abstractions all. Instead of "the Truth," one is forced in Chinese [and science] to speak of the set of all claims/concepts that are true by definition or as supporting evidence indicates, but "the Truth" definitely feels better to believe in, so thank you again Plato. The linguistic assertion that "I think" suggests that I am an object, an entity, a Self. "Thinking, therefore being" implies a functioning brain engaged in concept forming, which, yes, implies a brain able to form thoughts, which, like rocks, involves "being." So insofar as I endeavor to think, an activity involving a high error rate, perhaps I'm a verb, and not an object. Perhaps in ancient China there was a village idiot that duplicated Descartes's achievements in philosophy. That would be "a village idiot" as evaluated by other Chinese, hence it follows that their failure to recognize true genius means almost all Chinese are idiots, QED (as we often-wrong Indo-European types like to say).

For the Greeks, following Plato, the true nature of reality was in the abstract dimension of Forms; for the Chinese, the true nature of things was the Tao as expressed in the material world. The two languages seem to have encouraged these divergent worldviews, with Greek pushing its speakers toward abstraction and Chinese reinforcing a material view of the nature of reality.

Just as important as what the Chinese language lacks are the features it possesses that don't exist in Indo-European languages. When Westerners hear Chinese people speak, the language is frequently perceived as having a singsong quality, as though all kinds of emotional changes are being expressed from one moment to the next. This is because Chinese use tonal qualities to change the meaning of a word. In Indo-European languages a word is something purely conceptual. The split between word and tone reinforces the Western split between mind and body, reason and emotion. To a Chinese speaker there is no split between what a person says and how a person says it.

The Greeks were particularly concerned with finding underlying truths made certain by formal logic, meaning true by definition. In place of logic, the Chinese use dialectical thought to iterate towards understanding the universe, gaining insights through studying how everything is related to everything else, which is a foundational requirement of systems science. Reality is never fixed but constantly shifting; only ideas can become fixed as certitudes in believing minds for as long as they go on believing. Heraclitus agreed that change and uncertainty was foundational, a view that was anathema to Platonists (and Neoplatonist Christian apologists). Opposites naturally compliment each other to coexist in harmony, even though they could be falsely viewed as diametric opposites in the real world because they appear as conceptual opposites to logic chopping minds that know only words, words, words. Concepts representing apparent things are understood to be not the thing itself. Nothing exists in isolation but rather is integrated within a complex web of relationships.

As a result of these principles, Chinese science achieved different insights than the Greeks, who focused more on objects isolated [conceptually by mutual agreement] from their context, which is what works in silo science. The Chinese, by contrast, viewed everything as existing in a field of forces and achieved a deeper understanding of topics such as magnetism, acoustics, and gravity, which is what works in systems science via holism over reductionism (which at times is just the methodology that works). Western logic favors either/or thinking while systems science favors and/both thinking, as exemplified by Laozi.

The tendency of the Greeks [actually Plato], to universalize and the Chinese to contextualize led the two cultures to different conceptions of human nature. The abstracting inclination of the Greek mind, reaching its apotheosis in Plato [per Neoplatonists, as Carneades was more apotheosis], caused them to seek the ultimate Truth outside the material world in a putative eternal dimension of Forms [as for apotheosis, Aristotle increasingly distanced himself from Plato, becoming more empirical as he grew older, and Carneades, tenth head of Plato's Academy, was decidedly not a Platonist, hence latterday Greeks did not view Plato as the height of Greek thought like those today who over rate him secondary to the destruction of the works of non-Christian serving Greek thinkers]. This paralleled a dualistic conception of the human being, with an immortal soul imprisoned temporarily in a polluted body. In contrast, the Chinese sought reality within an organic view of the universe, looking for how each part harmonized within the entire system. The Chinese word xin, which literally means "heart," is also translated as "mind." It incorporates the physical organ of the heart but also much more: the full panoply of conscious experience, including emotion, thought, intuition, and desire. "The heart-mind [xin] is nothing without the body," wrote Chinese philosopher Wang Yan-ming, "and the body is nothing without the heart-mind."

The Chinese conception of xin led them to reject the idea that reason, separate from emotion, had inherent value. Far from deifying reason, the Chinese identified it as a cause of human difficulties [cognitive pathologies]. Most humans were viewed as pursuing their selfish and rationalistic desires, whereas a sage was understood to be in touch with his intuition, an integral part of the faculty of xin. The Chinese thus viewed a healthy approach to the human condition as one that integrated reason with intuition [as do working scientists, e.g. Einstein], seeing the unlimited pursuit of knowledge as positively dangerous.

With their embodied conception of xin, the Chinese made no distinction between physical health and mental or 'spiritual' health. While the ancient Greeks (and yogis of India) viewed transcendence from bodily experience as their ultimate goal, the Chinese perceived harmonization with the Tao as something to be achieved through both mental and physiological methods. The Chinese, like the Indians, developed sophisticated practices of concentration, breathing, and movement, but they never saw these practices in terms of the mind exercising discipline over the body. Rather, body and mind were inherently integrated.

The Greeks' [Plato's] belief in an immortal soul as a person's true essence naturally led them to emphasize the importance of the [alleged] soul's continued existence after the body's death. The ancient Chinese would have none of this. Given their sense that the embodied xin was a person's essence, they gave little thought to the soul's continued existence after death. There was no heaven or hell, no punishment or reward meted out after death based on a person's activities during life. Zhuangzi considered it a grief that "when one's body is transformed in death, one's xin goes with it in the same way." With no interest in an afterlife, the Chinese preoccupied themselves with making the most of their present life. "You do not yet know about life; why do you concern yourself about death?" said Confucius. "The secret awaits for the insight by eyes unclouded by longing; Those that look with prejudiced eyes see only the outward container." —Laozi.

In the second millennium BCE, communities from Egypt to Mesopotamia were frequently bothered by bands of habiru, or "outsiders," described variously as mercenaries, thieves, or migrant laborers. Some of these habiru were enslaved and forced to work on the new capital of Pharaoh Ramesses II around 1250 BCE, but they escaped and made their way to Canaan. There, they settled down as sheepherders and farmers in isolated hill-country villages, accepting the name habiru for themselves, which eventually metamorphosed into the name they have been known by ever since: Hebrews. The creed of monotheism has so permeated modern cognition that we need to look deeply into history to identify its underlying assumptions and implications. While one pathway to monotheism began with those Hebrew villagers in the land of Canaan, another started out with the Platonic tradition of the the ancient Greeks [Plato]. The story of how monotheism took hold of the entire Western tradition is one of synthesis: between the charged religious drama of the Old and New Testaments and the dispassionate philosophizing of Plato and his intellectual heirs, which formed the unique amalgam we know as Christianity.

The early church fathers agreed that to know God it was necessary to have as little to do as possible with the ways of the flesh. Augustine, the most prominent church father, is generally viewed as setting the future pattern of European Christian thought. He viewed religion through the same Platonic lens as his predecessors Clement and Origen. The human body had been designed by the forces of evil to imprison the soul. Augustine added original sin passed on through the generations via desire for physical pleasure, with the most extreme and shameless manifestation in the sexual act. Augustine's life is often seen as the transition point from the classical world to the beginning of medieval Europe, ushering in an era when Christianity would dominate all aspects of Western thought. The inner struggles [pathologies] of the church fathers would set the stage for how virtually all Europeans for the next thousand years tried to make sense of their internal experience and their place in the cosmos, forcing them to view their humanness as fundamentally split along ideological and physical dimensions. In the Taoist view [and science] there is one reality, not two, apart from which not a thing is.

Descartes had a profound impact on modern Western thought. Along with Plato and Augustine, Descartes was a prime architect of verities still viewed by many as self-evident: that our thoughts constitute our essence and that the mind is separate from the body and is what makes us human. Descartes's dualism also forms the basis for industrial society's relationship with Nature, the natural world. If Mind is the source of our true identity, then our bodies, not to mention the physical world, are mere matter with no intrinsic value. Since no other entity possesses a mind/soul capable of reason, "I do not recognize any difference between the machines made by craftsmen and the various bodies that nature alone composes," notes Descartes. With this step Descartes completed the process, begun by monotheism, that eliminated any intrinsic value to the natural world other than to serve humans, the triumph of humancentric thought. The one fundamental truth everyone, including early scientists, could agree on was the sanctity of the human mind/soul in contrast to the rest of nature.

The Protestant movement put its own unique stamp on the split between reason and emotion by emphasizing the importance of cognitive control as proof of God's favor, which gave rise to their Protestant ethic. While secular views have spread, for better or worse, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, as they did in the third and second centuries BCE among the Greeks prior to their conquest, Christian memes still dominate in the West, with 84 percent of Americans believing in life after death (for them), and 82 percent believing in heaven and hell, if not Earth. The number of those who believe in a Flat Earth has tripled in the past decade, and human dominionism is alive and well for now as all endeavor to grow the economy of whatever country they happen to identify with. But not all share in the enthusiasm nor have viewed "progress" as an unquestionably good thing. "For the Earth is like a vessel so sacred that at the merest touch of the profane—it is marred, and when they reach out their hands to grasp it—it is gone" notes Laozi who also recognized a higher power than Self (though of this world only), but held little else in common with modern Anthropocene enthusiasts who are everywhere reaching out to grasp and puff their Selves out (and their imagined Other).

In 1361 BCE a young pharaoh came to believe in One True God, Aten. All his priests, however, believed Amun was the god of gods. Akhenaten, "the splendor of Aten" was the first monotheist, the first to insist that not only was his God better than your god, but his God was the only god that existed, that all other gods and goddess were not merely lessor, but they didn't exist and never had existed. This idea led to merciless persecution and religious intolerance, seen for the first time in human history. Akhenaten ordered that the name "Amum" be removed from all monuments, making Amun into an un-god.

Zoroaster's theological dogmatism was unparalleled in the ancient world, outdoing even that of Akhenaten, until the next outbreak of monotheism: the Old Testament. The children of Israel are repeatedly commanded by Yahweh to show no mercy to those they defeat in the name of their Lord. "When the Lord your God delivers it unto your hand, put to the sword all the men in it. As for the women, the children, the livestock and everything else in the city, you may take these as plunder for yourselves. And you may use the plunder the Lord your God gives you from your enemies." —Yahweh. Such mercies were to be shown only to distant cities. For those living within the homeland of the Israelites, "do not leave alive anything that breathes," lest they influence the children of Israel to stray from their worship of Yahweh. In the new monotheistic paradigm, a war of conquest for power shifts to a war of ideology—a holy war.

In contrast to the Israelites, the Roman Empire did succeed in establishing their military power across much of the ancient-world. When they did, it was a challenge for them to come to terms with the absolutist refusal of monotheistic religions to tolerate different viewpoints. It is not surprising, then, that pagan thinkers and administrators became increasingly dismayed when Christianity infiltrated the empire and began enforcing unprecedented control over the beliefs and practices of everyone around them. The rivalry between Christian and pagan effectively came to an end with the emperor Constantine, whose rule fused the power of Rome with the theological absolutism of Christianity, creating the legacy of Christian domination that would define the European experience for the next millennium and a half.

Like India, China demonstrated a tolerant approach to religious beliefs throughout the premodern period. The emperors of China and India were similar in that they both did not regard religious differences a justification for war. The Chinese propensity for harmonization of different points of view reveals itself throughout their long history of evolving belief systems. As Zongmi, a ninth-century scholar, when asked by a student about the differences between Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, said "For those of great wisdom, they are the same. On the other hand, for those with little capacity they are different. Enlightenment and illusion depends solely on the capacity of man and not on the difference of teaching."

Buddhism gradually spread into China from India, reaching its zenith during the Tang dynasty (618-907), when it became an integral part of the Chinese cultural and political system. Toward the end of the Tang dynasty, a backlash occurred. The Chinese government turned on Buddhism in an attack known as the "Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution." What is notable about this persecution is its contrast with the monotheistic experience: no executions, no tortures, no burning at the stake, in contrast with the ruthless slaughter and mayhem associated with monotheistic persecutions.

After Jesuit missionaries came to China, the Pope expressly forbade missionaries to show any tolerance for traditional Chinese practices such as paying homage to Confucius or honoring the ancestors. The Kangxi emperor noted, "Reading this proclamation, I have concluded that the Westerners are petty indeed. It is impossible to reason with them because they do not understand larger issues as we understand them in China.... To judge from this proclamation, their religion is no different from other small, bigoted sects of Buddhism or Taoism. I have never seen a document which contains so much nonsense."

Chapter 14: Discovering the Principles of Nature in Song China

In the time of the Song dynasty (960-1279), China was by far the most developed region in the world, with the most advanced technological know-how. Woodblock printing had been used for centuries. The recent discovery of gunpowder was transforming the military with bombs, grenades, and cannons. Chinese ships were larger and more seaworthy than those of any other nation and navigated the open seas using the magnetic compass. Inland, they transported agricultural and industrial commodities through an extensive fifty-thousand-kilometer canal network. The Song economy was further boosted by the introduction of state-issued paper currency in 1024—about eight hundred years before it became widespread in Europe.

Fueled by its prosperity, Song society nurtured an open spirit of intellectual investigation that invites comparison with the European Renaissance. The polymath Shen Kuo conceptualized true north from magnetic north and formed hypotheses of gradual climate change and geological land formation from his study of fossils. This era achieved such great advances in thought that it is recognized as the golden age of Chinese philosophy which developed a systematic approach to understanding the cosmos. Instead of seeking the source of meaning in transcendence, like their Indian and European contemporaries, Song thinkers found intrinsic value and meaning from the world around them, as systems scientists do today.

Unlike other iconic Chinese innovations such as the compass, paper, printing, and gunpowder, the achievements of the Song philosophers have remained relatively unacknowledged. Apart from small groups of scholars cloistered in academic institutions, their contribution to human understanding remains virtually unknown in the West. We would do well to consider the insights of this group of thinkers and its relevance to the philosophical, spiritual, ethical, and existential challenges facing our modern society.

A dialog between Taoists and Confucians about the Tao, what was it and how best to harmonize with it, continued through the first millennium but was joined, and eventually transformed, by a third tradition that originated outside of China: Buddhism, which reached China early in the first century of the Common Era, and by the fourth century, it was flowering there. When Buddha lived, the Indian subcontinent was under the influence of Vedic thought, having its origin in Indo-European Aryan conquest, which remains dominant in India where Buddhism has died out. Buddha's non-dualistic teachings, however, could grow in Chinese soil along with its native non-dualistic Taoist teachings. Confucianism remained dominant as state sponsored religion, though those of high capacity often considered Taoist and Buddhist insights.

The Buddha's "middle way" found a warm welcome in Chinese culture which had no dualistic conception of the universe to overcome. Instead, many Chinese felt a deep affinity with the Buddhist doctrine of dharma: a recognition of the indivisible integrity and harmony of the universe, in which all parts are interdependent. This sounded so much like the Tao that, when Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese, the word Tao was simply used to translate the word dharma. After a while, educated Chinese became so comfortable with Buddhism that many believed it must have originated in China.

Although Buddhism, which is not necessarily what Buddha thought or taught, had absorbed some properties of the Vedic dualistic paradigm, such as the concept of nirvana, a state of peaceful bliss available through prolonged meditation in which bodily sensations dissolve and sensual desires disappear. Along with this emphasis on transcending the physical world, some schools of Buddhism continued to teach the core Vedic principle that the phenomenal world was only an illusion and that once practitioners became enlightened, they would recognize the emptiness of all things. A visitor to a Buddhist temple might hear endless chants of "empty, empty, empty" echoing eerily through the hallways. As in Confucianism and Taoism, the beliefs of followers may not reflect those of Confucius, Laozi, or Buddha. The Neo-Confucians sought a middle ground between them.

The idea that the ultimate ground of reality was emptiness made little sense to a culture steeped in the notion of harmonizing with the flow of the universe. One critique of the time eloquently captured the contrast between the Chinese and Vedic influenced Buddhist traditions: "Buddhism looks upon emptiness as the highest and upon existence as an illusion. Those who wish to learn the true Tao must take good note of this. Daily we see the sun and moon revolving in the heavens, and the mountains and rivers rooted in the earth, while men and animals wander abroad the world. If ten thousand Buddhas were to appear all at once, they would not be able to destroy the world, to arrest its movements, or to bring it to nothingness. The sun has made day and the moon night, the mountains have stood firm and the rivers have flowed, men and animals have been born, since the beginning of time—these things have never changed, and one should rejoice that this is so. If one thing decays, another arises. My body will die, but mankind will go on. So all is not emptiness!"

Buddhism had arrived in China with a comprehensive explanation of the cosmos, which included the concept of reincarnation, another Vedic concept that had hitched a ride from India. The Song philosophers lacked an equivalent systematic worldview to offer as an alternative. The Confucian and Taoist traditions provided elaborate descriptions for how the manifest world worked, but they had rarely ventured to describe the ultimate ground of reality. Now, as the Song philosophers critiqued Buddhism, they were forced to come up with their own fundamental explanation of reality. They called their new way of thinking "The School of the Study of the Tao," [or Nature via systems science which includes and harmonizes all silo sciences] emphasizing its roots in traditional Chinese Thought [a political requirement as Confucianism was the state religion/ideology], while, in the West, their philosophy is known as Neo-Confucianism.

Since Confucianism was the state religion, the Song philosophers were intent on establishing the primacy of Confucianism over Taoism and Buddhism, both of which they had to view as "wrong" or erroneous. But Taoism and Buddhism had both so pervaded Chinese thought over the previous millennium that it proved impossible to eliminate their influence—and this is, ironically, the very thing that made the Neo-Confucians' philosophy so powerful. In their attempts to promote Confucianism and refute Buddhism and Taoism, they ended up creating a triumphant synthesis of all three traditions, weaving crucial elements of each into a philosophical fabric that was far more comprehensive than any alone could have been. [The Song philosophers had to serve their SYSTEM. Had they not, the focus might have been on integrating Buddhism and Taoism as in Ch'an (Huineng, Huángbò, et al. who were not SYSTEM serving wordsmiths/concept-mongers), with little or no enthusiasm for serving the social control system of a complex society.]

If emptiness was not the ultimate ground of reality, what could it be? Zhou Dun-yi scoured the Tao Te Ching of the Taoists and the I Ching of the Confucians. He proposed that the Taoist "Unlimited" was the same as the Confucian concept of "Supreme Ultimate," and that both were other than "Emptiness." From there, Zhou felt he could describe how everything in the universe arises. The Supreme Ultimate produced the yin and yang modes of existence, which, in turn, generated five elemental states known in Chinese lore as fire, water, earth, metal, and wood. These interacted with each other to create the "ten thousand things"—the myriad manifestations of the material world.

Zhang Zai countered the Buddhists by focusing on the traditional idea of energy. Instead of emptiness, Zhang declared, the universe was filled with energy [qi], the fundamental energy that underlaid all the processes of the universe, which, in Zhang's view, was indestructible and continually transforming, and through its dynamic, ever-changing nature arose what he called the Great Harmony of the Tao. He was fascinated by the way in which this Great Harmony was an organic unity and yet always different. "The Principle [li] is one," he observed, "but its function is differentiated into the many"—a vision of the one-and-many that echoes the insights of early Vedic thinkers as well as the cosmology of ancient Egypt and would become a foundational principle of Neo-Confucian thought.

What was this mysterious "Principle" that encompassed all things? Two brothers, Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi, took it upon themselves to ponder this question. Each tried to make sense of the "principle"—the li—that their uncle, Zhang Zai, had identified as pervading all things. "All things under heaven can be understood by their li. As there are things, there must be principles of their being. Everything must have its principle."

A century would pass between this first wave of thinkers and the philosopher who put their insights together to form an explanation of the universe that would not only refute the Buddhist view of emptiness but provide a basis for the Chinese understanding of the cosmos for centuries to come. His name was Zhu Xi, and what he accomplished was an extraordinary act of synthesis and transformation. He took Zhou Dun-yi's interpretation of the Supreme Ultimate, and he wove these elements together into one coherent system.

Zhu Xi described the universe as being fundamentally composed of both qi and li, energy and natural laws. Qi was the term for all the energy and matter, as manifest energy, in the entire universe, and li was the term for how that energy and matter was organized [how complex systems self-organize], the patterns that work to organize complex systems [MPP—Maximum Power Principle] as distinct from those that fail to. The interplay of energy and natural laws determined every aspect of reality. "Throughout the universe," declared Zhu Xi, "there is no qi without li, nor li without qi." One cannot exist without the other because each can only be defined in terms of the other, in much the same way that a rectangle cannot exist without both width and length. The underlying concept is that matter or energy can't exist without being organized into a hierarchy of systems within subsystems.

Ever since Westerners came across these ideas there has been a tendency to reframe the concepts into the dualistic paradigm that Plato established so firmly in Western consciousness. Plato's division of the cosmos into a tangible dimension and abstract dimension of Ideas was used to neatly map the Neo-Confucian terminology accordingly: qi represented Matter and li represent the Idea or Form.

It took a Joseph Needham to confront head-on the orthodox Western interpretation of li and qi in the middle of the twentieth century. Needham first made a name for himself as a biochemist. In mid-career, he became fascinated by China and went on to publish a series of volumes entitled Science and Civilisation in China, which transformed the conventional Western view of Chinese history that had previously considered China a backward and ineffectual society.

Needham was well versed in the orthodox Western philosophical tradition, but he had also learned to think as a biologist and was therefore unusually well-equipped to offer an alternative perspective. He pointed out that the dualistic splits of Western thought—body versus soul, material world versus eternal God—simply didn't exist in the Chinese cosmos, and that the Platonic Form versus Matter interpretation of li and qi was therefore "entirely unacceptable." Li was not some metaphysical concept "but rather the invisible organizing fields or forces existing at all levels within the natural world." E.g. the laws/patterns of thermodynamics, evolution, information (DNA), et al.

Although laws are invisible, these organizing principles of systems could clearly be seen through their effect on energy and matter. Needham pointed out that, like the wind, li should not be thought of as a fixed pattern but rather a "dynamic pattern as embodied in all living things." The sum total of li creates systems not only more complex than we understand, but more complex than we can understand, which is not a mystery for mystery-mongers to write books about, but merely a cognitive limitation. An ocean wave breaking on the shore can be viewed as water in motion, as matter/energy [qi], while the various forces organizing the water into its dynamic wave pattern are the li, gravity, water cohesion, fluid properties....

Li also refers to patterns in time as well as space, patterns within patterns, systems within systems, and patterns that we create in our own minds through our patterning instinct. Li is perhaps best described as the ever-moving, ever-present set of patterns that flow through everything in nature and in all our perceptions of the world, including our own consciousness.

Li applies not only to the organic world but also to inanimate objects. Zhou Xi explained that li pertains to everything in the universe at different levels of complexity. It can relate to something as simple as a pen, the organizing principles of which are human-made, and equally well be applied to the unfathomably complex organization of Nature, the human brain, and all complex systems.

Einstein and heirs recognized the transmutability of matter and energy. Niels Bohr saw the complementarity of yin and yang as representing the dual characteristic of subatomic matter as both wave and particle, and incorporated the yin-yang symbol into his coat of arms. The early twentieth century Technocracy movement used the yin-yang too.

The findings of modern complexity science and systems biology have unearthed further correspondences with the Neo-Confucian concept of li and qi. Researchers from specialties as diverse as mathematics, climatology, and neuroscience have come to understand the natural world as a complex of different systems continually interacting with each other. They have identified universal features of these dynamical systems that remain valid across the entire natural world, from systems as vast as global climate to as small as a living cell—systems all. A common feature of these systems is that they self-organize to create a cohesive whole that cannot be completely understood by reducing the system to its elemental parts. The correspondence of these findings to the Neo-Confucian concepts of li and qi are more than superficial—they are intrinsic to the structure of both modern systems science and Neo-Confucian thought.

A characteristic feature of a self-organized system is that it remains stable even while the physical matter making up the system changes. A simple way to understand this is to consider a candle flame. As the flame burns, every molecule that originally comprises the flame vanishes into the atmosphere. Each moment, the molecules making up the flame are different, yet the flame remains an ongoing entity. In scientific terms, we can understand the flame's organizing principles in terms of the relatively stable relationship between the wax, the wick, the flame's heat, and the oxygen in the atmosphere. In Neo-Confucian terminology, we could say that the li of the flame remains stable even while the qi—the physical components—continually changes.

A similar relationship between li and qi applies when we consider ourselves as a complex, dynamical system. If you look at a photograph of yourself when you were a child, you recognize it as you, but virtually every cell that was in that child no longer exists in your body. This raises the question of what it actually is that forms the intimate connection between you and that child. The answer is the li. The qi has all changed, but the li remains stable: growing, evolving, but patterning its growth on the child's original principles of organization.

Some researchers have tried to place consciousness in a specific place in the brain, but the "li of consciousness" as one researcher notes is "A dynamic core [of consciousness] is...a process, not a thing or a place and it is defined in terms of neural interactions, rather than in terms of specific neural location, connectivity, or activity."

Just as li was understood by the Neo-Confucians to apply to every aspect of the universe, so systems scientists recognize that systems principles apply equally to everything in the natural world, li as patterns in an energy flow. These insights arose in the particular context of Song dynasty China and carry the unique linguistic and cultural characteristics of that time and place; but much of what Neo-Confucian thinkers discovered about how li informs values and life experiences remains valid, offering wisdom that can be applied to our modern era.

A founding figure in dynamical systems theory, Gregory Bateson, once famously wrote: "What is the pattern which connects all the living creatures? The pattern which connects is a metapattern. It is a pattern of patterns. It is that metapattern which defines the vast generalization that, indeed, is patterns which connect." A thousand years before Bateson, Zhu Xi pondered the metapattern connecting all other patterns and became convinced that it was the Tao. He understood the Tao as the general set of principles containing all the li of the universe. "The word Tao," he said, "is vast and large. The li is minute and detailed." He recognized that it is naturally easier to discern some of the patterns making up the cosmos than the ultimate metapattern. "The Tao," he reflected, "is...so distant that even sages cannot...comprehensively understand it.... But the li that is the reason for things, though hidden and not visible, can nonetheless be known and acted upon."

For Cheng Yi, "the Supreme Ultimate is the Tao." But Zhu Xi insisted on one crucially unique characteristic of the Supreme Ultimate: it consisted of all the li without any qi. The difference, then, between the Supreme Ultimate and the Tao was that the Supreme Ultimate represented the underlying patterning of the universe as possible patterns prior to its actual existence, whereas the Tao represented the tangible manifestations of the ever-changing, infinitely complex interactions between li and qi that comprise the cosmos.

The belief in immanent divinity throughout the entire universe is known as pantheism, and, during the period of Christian dominance in Europe, it was viewed as a heresy sometimes punishable by death. In the modern era, an experience of the ultimate oneness of the cosmos is liable to be dismissed as "mystical" and not considered valid in mainstream scientific discourse. The Neo-Confucians, on the other hand, came to this understanding of the universe by way of a systematic exploration of the implications of a cosmos consisting entirely of li and qi. "When we speak of heaven, earth, and the myriad things together, there is just one li," wrote Zhu Xi. "When we come to humans, each has his or her own li.... Although each has his own li, each nonetheless emerges from a single li." Or "each of us has our own unique coherence, which, nonetheless, emerges from a single coherence." We are such patterns that work as selected for within complex systems over the millennia.

We live in a world dominated by two incompatible worldviews, both of which are the result of dualistic thinking. The monotheism of Judeo-Christian-Islamic belief that posits an intangible dimension from which derives the ultimate source of meaning. The other worldview is that of scientific reductionism, silo science, that sees reductionist science as the only valid way of understanding the universe and rejects alternative holistic ways of inquiry, e.g. systems science. In the words of physicist Steven Weinberg, "The more we know of the universe, the more meaningless it appears." Many people, however, find themselves caught in the middle, rejecting dualism but sensing something greater than Self and Other, and they seek alternative explanations for meaning in their lives, which are frequently dismissed by silo science as incoherent.

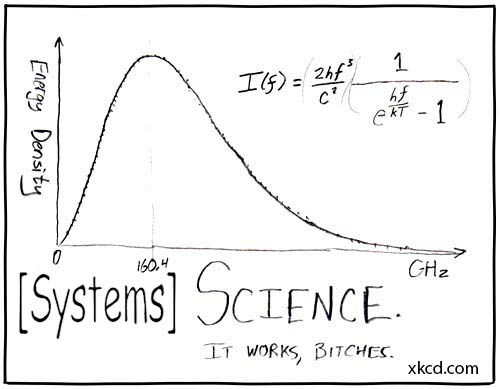

Systems science offers an approach to finding meaning in the cosmos that does not involve the artificial trade-off created by the dualistic paradigm. It invites connection with a source of meaning in a form consistent with scientific inquiry. With its conceptual foundation of matter/energy and the rules that work, patterns that are selected for that produce 'forms most beautiful and most wonderful that have been and are being evolved' within both genetic and memetic information systems. Systems science provides a coherent framework for systems-based interpretations of age-old Western philosophical issues such as how mind arises from the brain, what the basis of ethics and morality is, and how to live harmoniously and sustainably in the natural world.

In Albert Einstein's view, the religious feeling of the scientist "takes the form of a rapturous amazement at the harmony of natural law, which reveals an intelligence of such superiority that, compared with it, all the systematic thinking and acting of human beings is an utterly insignificant reflection." This intelligence, for the Neo-Confucians, was the self-organized creation of the natural world manifesting in what they called the Tao.

In Neo-Confucian thought, the great Western divide between science and spiritual meaning is nowhere to be found. Similarly, the dualistic distinctions between mind and body, knowledge and action, reason and intuition, disappear from view. In their place, we find an organic conception of the universe that shows disparate human experiences arising from the integrated and coherent whole. For the Neo-Confucians, achieving a deep understanding of the workings of the universe was equivalent to attaining a highly developed spiritual wisdom.

Patterns of thought in Europe were setting European civilization on a course that would result in global domination. Complex systems thinking about the cosmos, constructed as it is from an utterly different foundation than Western thought, but consilient with non-dualistic Eastern thought, permits connections to be made that are almost inconceivable in Western cognition. We've seen earlier how the very structure and vocabulary of the language we speak create mental patterns that encourage our thoughts to traverse certain pathways, which become so deeply rooted that we are not even aware of them. The Neo-Confucian system of thought and the macroscope of systems science offers a way to break out of this paradigm, providing new patterns of connectivity and building blocks of thought that invite a coherent way of realizing meaning in our lives.

What became of the Song dynasty and its Neo-Confucian cosmology? The Mongols finally dealt the fatal blow when Genghis Khan's grandson, Kublai Khan, laid waste to their last stronghold in 1279. Neo-Confucian ideas survived, however, but by the early twentieth century, when Western colonial powers established their stranglehold over imperial China, many Chinese intellectuals viewed the Neo-Confucian tradition as responsible for the debilitated state of their civilization.

Patterns of thought in Europe were setting European civilization on a course that would result in global domination. By the time of Wang Yang-ming's death in 1529, Europe was stirring, and the effects of this would have dramatic repercussions across the entire globe, creating the world structure [the Euro-Sino Empire] that we inhabit today. And then what? If Chinese systems scientists recover their li, and come to just say no to growth/empire-building, perhaps form a naturocracy (or taocracy), then harmony may prevail as humans eventually organize a complex society of interactive and interdependent watershed management units. Perhaps "eventually we'll have a human on the planet that really does understand it and can live with it properly" — James Lovelock, which is what Laozi envisioned. No biophysical laws of the universe will be broken if we endeavor to have a managed, prosperous way down, and come to avoid extinction.

Part 4: Conquest of Nature

For Francis Bacon, and other servants of the Industrial Revolution, Nature was to be "put in constraint.... Let the human race recover that right over Nature which belongs to it by divine bequest." And the aim of the scientist was to "hound her in her wanderings." He called upon humankind "to unite forces against the nature of things, to storm and occupy her castles and stronghold and extend the bounds of human empire." An even more divine lawgiver bestowed on humankind dominion over Nature. "Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth." As Francis Bacon notes, "Man, if we look to final causes, may be regarded as the centre of the world.... For the whole world works together in the service of man; and there is nothing from which he does not derive use and fruit..insomuch that all things seem to be going about man's business and not their own."

The perception of Nature as GIVING PARENT is found throughout the world in cultures of all levels of sophistication. Zhang Zai gave memorable expression to this vision when he wrote, "Heaven is my father and earth is my mother, and I, a small child, find myself placed intimately between them." With this familial view of the cosmos, the Chinese never experienced a drive to conquer Nature. Instead, as they further elaborated their worldview, they formed a sophisticated vision of NATURE AS ORGANISM, with a particular focus on the dynamic and holistic relationship between each separate organism and the whole. In contrast to Westerners, the Chinese didn't view humans as separate from nature. The idea that all of nature was created to serve humans, such a powerful underlying theme in Western thought, was seen as rather ludicrous. In contrast to the Western belief that Nature was created for them by a DIVINE LAWGIVER, the Chinese saw Nature as a self-organized system in which all the parts fit harmoniously together.

As Laozi notes, Chapter 29:

Those who would take over the Earth

And shape it to their will

Never, I notice, succeed.For the Earth is like a vessel so sacred

That at the merest touch of the profane—

It is marred,

And when they reach out their hands to grasp it—

It is gone.For a time some force themselves ahead

And some are left behind,

For a time some make a great noise

And some are held silent,

For a time some are puffed fat

And some are kept hungry,

For a time some are held up

And some are destroyed.But at no time will a man who is sane:

Over-reach himself,

Over-spend himself,

Over-rate himself.

By contrast, the Indo-European ideal was conquest, of other men and Nature, a policy that works for a time, but they, the empire builders, never, as history notes, succeed in shaping it to their will.

In 1405, Admiral Zheng set off from China with a massive armada, which over the next three decades and seven long voyages, Zheng and his forces would visit places ranging from East Africa to Arabia, Egypt, India, Sri Lanka and Sumatra. He could have done virtually anything he wanted to the places he visited: enslave the population, mine their mineral wealth, and entrench China's empire throughout the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean. Instead, he set up embassies in China with emissaries from Japan, Malaya, Vietnam, and Egypt. Apparently it was as unthinkable for Admiral Zheng to conquer and enslave the societies he visited as it was for Columbus and ilk to have set up embassies with the indigenous people he encountered in the New World rather than conquer entire continents, massacring and enslaving their inhabitants, instigate genocide and pillaging their natural resources.

Experts have long recognized the magnitude of the Scientific Revolution that transformed Europe. Why did scientific inquiry as a way of knowing, of finding things out, arise in Europe and not China nor the Islamic Empire that once spread from Iberia to India? China enjoyed a high level of technological and cultural sophistication. For a time, after vast deforestation, coal was used to power the industrial production of metal and glass. Why didn't that catalyze an Industrial Revolution? Islamic civilization, for several centuries, boasted some of the most advanced centers of learning the world had ever seen. Why did these not spark a transformation in scientific thought?

As chief spymaster in northwestern Iran for the caliph, it was Abul Ibn Khordadbeh's business was to know what went on in the world, those portions of it that mattered. He recorded his findings in The Book of Roads and Kingdoms, the earliest surviving book of Arab geography, which includes descriptions of the wonders of Asia all the way to Japan and the southern coast of India. One area that held no interest for him was Western Europe, which was good only for the occasional "eunuchs, slave girls and boys, brocade, beaver skins, glue, sables, and swords." A century later another Muslim geographer noted that Europeans were "dull in mind and heavy in speech, [and the] farther they are to the north the more stupid, gross, and brutish they are." Marco Polo, from the most advanced part of Europe, was yet transfixed when he came across the Chinese capital of Hangzhou, describing it as "without doubt the finest and most splendid city in the world,... anyone seeing such a multitude would believe it a stark impossibility that food could be found to fill so many mouths." Yet a few centuries later, Europeans were master conquerors of the world, beginning with their conquest of Nature (for a time). All who could read this, including in translation, are living in the conquest.

When the Roman Empire of the East (Byzantine Empire) fell in 1453 CE, thanks to emigrant Byzantine Greco scholars escaping the Caliphate (with as many books as they could), something of the Greek learning was revived, via the European Renaissance and Enlightenment, and lives on in the science and scholarship that followed and yet exists within the narrow confines of the all subsuming popular-growth-belief-culture of technoindustrial producers and consumers. But why were the Greco scholars not put to death as they would have been in the Caliphate? Well, religionists in Europe, emerging from their dark age, were easily impressed, and the scholars offered to serve without dwelling upon the incompatibility of free inquiry and belief-based ways of knowing (dogma). Few would rather know than believe, and the spreading of memes takes decades to millennia.

Bacon's vision of science included human dominionism, "Let the human race recover that right over Nature which belongs to it by divine bequest." Science could be, and therefore was, viewed as a handmaiden of empire and its religious control system. The implied non-centrality of humans in the universe by Copernicus and others (e.g. biologists) was eventually overlooked as science and technology was clearly a boon to empire and profit. With the Industrial Revolution, the services of theologists needed to justify inequity (as within the Feudal system) was no longer needed as economists came to provide that service. Science was valued, as God had been, "for the milk and cheese and profit it brings." ["Most men love God the way they love their cow, for the milk and cheese and profit it brings." —Meister Eckhart]

But within the Islamic Empire, there was Islamic science, which involved studying the Quran. The Greek learning was of interest to a few Muslims, called faylasuf (philosophers), but was known as "foreign science" to distinguish it from true science. When the Islamic Empire reached from Iberia to India, it fragmented into multiple polities, but religion remained constant and dominant. Those who spread Islam were military men, empire builders, who often lacked interest in religious certitudes. Some embraced the Greek learning and favored Muslim scholars who took an interest in it. After the expansion of empire there was great wealth and some was used to support a golden age of learning in some areas of the empire, but the foreign science was never embraced by the vast majority and was soon marginalized unto non-existence. The greatest 'philosopher' of Islam became al-Ghazali who knew enough philosophy to disparage it, to write The Incoherence of the Philosophers, in which he explained that as man had been created to seek only the kind of knowledge that brings him closer to God, that religious knowledge was of the highest value, with all other forms of knowledge holding a subordinate position. When natural science was used to aid religious observance, such as establishing the religious calendar, then that was its proper service, but when used to determine general properties of the natural world, scientists were wasting their time that should be spent reading the Quran. As al-Ghazali and, well, just about everyone else came to pray five times a day, "May God protect us from useless knowledge."

Al-Ghazali also saw mathematics as dangerous because of its reliance on logical proofs. He worried that people might become so impressed with the precise techniques of mathematical logic that they might use it to try to prove the existence of God (and fail), "How many have I seen who err from the truth because of this high opinion of the philosophers and without any other basis?" Reasoning became blasphemy: "Few there are without being stripped of religion and having the bridle of godly fear removed from their heads... [the faylasuf commit] blatant blasphemy to which no Muslim sect would subscribe." The religionists agreed and still do, hence only Islamic 'science' prevailed. Within three decades of the publication of the first printed books in Europe in 1455, the most powerful Muslim ruler, the Turkish sultan, banned the publication and possession of any printed material. The ban was repeated and enforced by later sultans, with such success that the first Arabic-language books were printed in Europe by Christians in the early sixteenth century, and it was only in the nineteenth century that the ban was finally lifted in Muslim countries.

The reason, then, that the scientific achievements of Islamic civilization never caused the revolution in thought that occurred in Europe is evident. Muslim breakthroughs in scientific thought, impressive as they were, tended to be sporadic and clustered in communities that protected scientific thinkers from the mainstream culture. The thrust of Islamic cognition was aimed toward following the divine words of the Quran and submitting unquestioningly to faith whenever it might conflict with the findings of reason. It was focused in an opposite direction from the relentless querying of natural phenomena that was required for a revolution in scientific thought to occur. In Western culture science was tolerated for its service to the bottom line, but was otherwise marginalized in society, including academia.

So science as a way of knowing, of inquiry, of finding things out, didn't take hold in the religious soil of the Islamic Empire. But why not in China with no belief in an omnipotent god and no conception of any conflict between intuition and reason? The advanced state of society in fourteenth-century China inspired awe in those few foreigners who managed to travel there. Chinese civilization had all the key technologies that Europeans later saw as a foundation for their own scientific revolution. In 1620, Francis Bacon observed that three technologies had transformed the face of European civilization: printing, gunpowder, and the nautical compass. All three were invented by the Chinese and were in use by the time of the Song dynasty.

Beyond these three key technologies, an entire array of industrial and economic achievements gave China a gigantic lead over the rest of the world. The scale of iron production in China was, in the words of one historian, "truly staggering," reaching a level of 125,000 tons a year by 1076, as compared with the 76,000 tons produced in England in 1788 early in the Industrial Revolution. The Chinese government started printing money in 1024.

The sophistication of Song society extended into the realm of intellectual discovery. While Neo-Confucian philosophers were synthesizing the great traditions of Chinese thought, other intellectuals applied critical thinking to make remarkable progress in areas as diverse as medicine, geography, mathematics, and astronomy, with publications such as the first known treatise on forensic medicine and a geographic encyclopedia with two hundred chapters. Cartography achieved greater precision than ever before, with a vehicle for measuring road distances designed and built in 1027. In mathematics, Qin Jiushao began using the zero symbol in the fourteenth century, around the same time that Arabic numerals first appeared in Italy.

In the fourteenth century, China had reached the threshold for a scientific and industrial revolution, so why did the Industrial Revolution not occur in China when almost every element that economists and historians consider needed was in place? Why did the fossil-fueled Industrial Revolution occur in eighteenth century England and not fourteenth century China? Why didn't the Chinese look about them and see a planet for the taking?

We Indo-European types assume that not using science and technology to achieve world domination is a failure. We ask why the Chinese failed, when the failure to question assumptions is our own. Perhaps world (or regional) conquest involves only short-term benefits to a few, for a time. Those taking a longer view seek to live long and prosper by living in harmony with their planetary life-support system. Clearly the China of today has been subsumed by the Indo-European growth hegemon, along with many other peoples, but it is not too late to take back our hunter-gatherer heritage of seeking to live in harmony with Nature.

Systems science, along with ancient wisdom often learned the hard way, can best inform our human endeavors to live properly on the planet. The problem of living in complex societies has yet to be solved (with the possible exception of the Kogi). All of the information acquired by past complex societies, the up to the ten percent or so that is known, is now at risk of ninety to one hundred percent loss, along with all we've learned in the last three hundred years, as usual, if we fail to manage our descent to a non-fossil-fueled world. We are at risk of losing 100 percent of human genetic information in gametic form, and 100 percent of the information acquired in the past seven thousand years of memetic evolution. Alternative to managed descent is chaotic collapse as usual, so let us consider a prosperous way down instead.

Most of the ideas above are Lent's, but not all (which are therefore probably wrong), so read the book at least once: The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning 2017. Aside from overrating Plato as is nearly universal in the West, Lent underrates reductionist silo science, with its materialist, determinist, and evidentalist ways. Lent is for systems science, but seems to view it and silo science as an either/or offering rather than an and/both way of doing science, of endeavoring to love and understand the universe. Without reductionist silo science there would be no systems science as there would be no dots to connect. Dawkins is seen as having misspent his life popularizing his reductionist views, misinforming an unsuspecting public. Dawkins is not a systems scientist type. That doesn't mean he's wrong. He could be, about everything, but assessing his science should be an evidence thing. Lent seems to see science as primarily a rationalist endeavor, as in its early days it was, and that science arose in the West may have much if not everything to do with Neoplatonic Christian rationalism, thank you very much empire-building Christian rationalists. Science is not so much a rational endeavor, however, as an evidentual game where those who listen to Nature get extra points by passing on their memes. Only a Neoplatonist would go on at length about human rationality, as if something to brag about, without noticing our impaired ability to find and face evidence (aka reality). Still, there is much of high value for the considering, so read the book, bitches.

Most of the ideas above are Lent's, but not all (which are therefore probably wrong), so read the book at least once: The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning 2017. Aside from overrating Plato as is nearly universal in the West, Lent underrates reductionist silo science, with its materialist, determinist, and evidentalist ways. Lent is for systems science, but seems to view it and silo science as an either/or offering rather than an and/both way of doing science, of endeavoring to love and understand the universe. Without reductionist silo science there would be no systems science as there would be no dots to connect. Dawkins is seen as having misspent his life popularizing his reductionist views, misinforming an unsuspecting public. Dawkins is not a systems scientist type. That doesn't mean he's wrong. He could be, about everything, but assessing his science should be an evidence thing. Lent seems to see science as primarily a rationalist endeavor, as in its early days it was, and that science arose in the West may have much if not everything to do with Neoplatonic Christian rationalism, thank you very much empire-building Christian rationalists. Science is not so much a rational endeavor, however, as an evidentual game where those who listen to Nature get extra points by passing on their memes. Only a Neoplatonist would go on at length about human rationality, as if something to brag about, without noticing our impaired ability to find and face evidence (aka reality). Still, there is much of high value for the considering, so read the book, bitches.