MONDAY, OCT 31, 2022: NOTE TO FILE

Overpopulation Isn’t a Threat

A late night ripple

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: INQUIETUDE, FROM THE WIRES, DEATH IS NEVER HAVING TO SAY YOU EXISTED

Abstract: I do not recall a day passing that did not end in a sleep option I couldn't refuse. Last night sleep was not an option. I was likely not in a normal state of mind. Screaming would wake the wife, so I typed.

COOS BAY (A-P) — An article was shared on a listserv of those who think overpopulation is a threat. It claimed that overpopulation, and concerns for depopulation (such as Elon Musk has), are certainly not a threat. Thomas Maltus and Aldous Huxley (and his brother) had concerns, but today no properly educated person should be concerned, because:

The article is at the end of this note, but first I will confess that for some reason I did not sleep last night. Instead I ended up typing to make a late night ripple, occasioned by the realization that no one would notice. In the Kingdom of the Sleepwalkers, one who would rather not is an annoyance.Overpopulation isn’t a threat

Elon Musk needs to read Aldous Huxley

BY ALISON BASHFORD

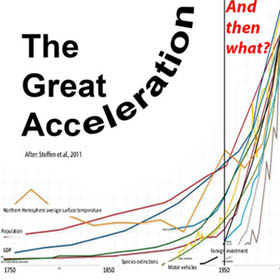

I have argued that 1972 was humanity's "Huston, we have a problem" year. It was perhaps the first "scientists' warning," the one that was unintended, an emergent warning from those who were not sleepwalking, who had noted the Great Acceleration of 1950 and wondered, "And then what?" The increasing realization of our and-then-what was coming into focus in 1972. The few were still wide-eyed, awake, and increasingly concerned if not for themselves, then for posterity. We collectively now are approaching our and-then-what answer this century, evermore cluelessly unaware of the answer that cometh.

I have argued that 1972 was humanity's "Huston, we have a problem" year. It was perhaps the first "scientists' warning," the one that was unintended, an emergent warning from those who were not sleepwalking, who had noted the Great Acceleration of 1950 and wondered, "And then what?" The increasing realization of our and-then-what was coming into focus in 1972. The few were still wide-eyed, awake, and increasingly concerned if not for themselves, then for posterity. We collectively now are approaching our and-then-what answer this century, evermore cluelessly unaware of the answer that cometh.------------------------------

Good to hear from Aldous and Julian Huxley via a Laureate Professor of History at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. Published by UnHerd, a work of two dozen mostly less than thirty-somethings, founded in 2017 by conservative British political activist Tim Montgomerie who departed from UnHerd in 2018. The 'About UnHerd Mission Statement' updates to the now.

"UnHerd aims to do two things: to push back against the herd mentality..., and to provide a platform for otherwise unheard ideas, people and places.... Societies across the West are divided and stuck, and the established media is struggling to make sense of what’s happening. The governing ideologies of the past generation are too often either unquestioningly defended or rejected wholesale. It’s easy and safe to be in one or other of these two camps – defensive liberal or angry reactionary.... We want to be bold enough to identify those things that have been lost, as well as gained, by the liberal world order of the past thirty years.... We are not aligned with any political party...."

The story is: You invite Aldous, Julian, and Elon Musk to dinner and report on their conversation about human population, and title your offering 'Overpopulation isn’t a threat: Elon Musk needs to read Aldous Huxley'. Okay, the conversation is of interest, and the author gets the last paragraph:

"As the planet approaches eight billion, the change in fertility rate since the Huxleys’ time means we need not be alarmed, as they were, by global 'overpopulation'. Nor should we worry about an incorrectly named global 'depopulation'. What we really need to be alarmed by are crude rationalisations for women to breed more. There lie the truly sinister lessons of history."

I would have added a bit more depth perspective by also inviting H.G. Wells to the dinner. He had clearly expressed his population growth concerned in his 1933 The Shape of Things to Come. Aldous neglected to read Wells' The Time Machine when it was published (he was one year old, so I'll cut him some slack).

The soon to tick again at 8 billion clock is looking so déjà vu (as I recall 3 billion 1960, 4 billion 1974, 5 billion 1987, 6 billion 12 October 1999). It is again October 31, 2011, and I'm listening to an NPR (National Public Radio) bit on the population clock ticking to 7 billion. It was another "yes, there are reasons to be concerned, but..." story, and I recall exactly the moment, like when I heard of JFK getting shot or the Twin Towers coming down.

I was working in my shop and the story ended with the usual lame assurance, something like "yes, there are now 7 billion humans on the planet, but in Azerbaijan a team of scientists are studying the problem and they think that soon...." and everyone (almost) listening relaxes knowing that somewhere, some really smart people are aware of and working to solve whatever the problem is that may seem problematic and troubling. "Meanwhile, the pace of planetary destruction has not slowed. And in Washington, Senator Haggle said that GDP...".

I realized that the media could only tell the same story, and so always had and will (and so I stopped listening). The only bit I didn't know in 2011 was what day of what month the clock would tick 8 billion (per consensus of UN). I would have been willing to guess the year (2023) and would not at all have been surprised to be off by a year, but that's not news. The news flash that would matter, one that could only come from a non-human like Klaatu writing for a newsletter a few on her home world read: Humanity's Accounting of Itself: Not Even Wrong.

-----------------------

Elon Musk needs to read Aldous Huxley

BY ALISON BASHFORD

The thing is, though, that Elon Musk is the future that the brilliant Huxley brothers spent their lives imagining; Aldous most famously in Brave New World (1932) and science-communicator Julian in a thousand books and articles and broadcasts on the quantity and quality of the human race on planet Earth.

Aldous and Julian would wonder why Mars was still so interesting for someone as clever as Musk. Human habitation of proximate planets was already an old idea for their generation. And not just as a science fiction trope. Emigration to the moon and Mars was tossed around all the time as a possible solution to one of the Huxley’s key political discussion points: overpopulation. Expenditure on settling other planets, Julian was convinced, would do nothing to alleviate the poverty that such crowding brought on Earth. His eminent brother Aldous was also firmly earthbound: neither population, nor hunger, nor land problems were going to be addressed by looking outward from Earth to the celestial bodies.

The trio would, inevitably, talk about population. Musk would probably tell them that, any day now, the world’s population will tick over to eight billion. Julian and Aldous would sit back and look at one another, shocked. In their time, they were both A-list speakers and lobbyists on the great post-war problem of overpopulation. But they had only imagined a future of up to four billion or so.

It is impossible to overstate the whole-Earth scale of the population problem in the years after the Second World War. The planetary crisis, then, — one of energy consumption — was not just similar to our own Anthropocene-crisis, but its direct antecedent. Julian and Aldous Huxley’s generation watched regional and global rates of net population growth accelerate in a manner unimaginable even to their grandfather, the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley. “Darwin’s bulldog”, a fierce supporter of Darwin’s theory of evolution, was already worried in the late 19th century.

In 1957, Julian put it in terms of doubling: one billion in the mid-18th century, two billion by the mid-Twenties, and at its Fifties rate, he forecast, four billion by the Eighties. His brother put the same idea differently. “On the first Christmas Day”, Aldous wrote, there were about 250 million humans; this grew only slowly, so that when the Pilgrim Fathers landed at Plymouth Rock, there were perhaps 500 million. By the time he wrote Brave New World in 1932 there were almost 2 billion people on the planet. Just 27 years later, when he revisited his dystopia, human numbers were approaching 3 billion. That was the figure that sent the Huxley brothers, like so many others, into intellectual and political overdrive.

Aldous wrote Brave New World Revisited in 1958, a non-fiction book naming something that was for him far more terrible than the fictional world he had created decades earlier: “The Age of Overpopulation.” For the Huxley brothers, world population growth was leading inexorably toward a catastrophic planetary future.

At my table, Musk might then lean forward and tell the Huxley brothers that as we approach eight billion on planet Earth in 2022, the average fertility rate has declined to 2.3 births per woman. That’s when the dinner party would either fall apart or come alive. For Elon Musk, this fertility rate is one of the great near-future problems. He tweets: “Population collapse due to low birth rates is a much bigger risk to civilisation than global warming.” He is not alone. We’ve heard quite a bit about an apparent cataclysm, for example in Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline, by Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson. In the Huxley era, similar catastrophic books were on the shelves, but they sold under titles like “Standing Room Only”, “Overfill” and “The Population Bomb”.

For Aldous and Julian Huxley, the astonishing fertility rate of 2.3 would be a breathtaking achievement. This was everything they had worked for. Planetary catastrophe had been averted! The future of humans on Earth, safe. Immodest Julian would think that the world had been wise, read his thousands of talks and books and papers on the unprecedented disaster that was population growth, and acted. The Huxley brothers simply couldn’t and wouldn’t understand how this decline could possibly be construed as a global problem.

Late in their lives, on this matter, the brothers were twinned: the same arguments, the same catastrophe, the same popular deployment of Huxley science and politics in every register and outlet possible. While Julian was writing articles on overpopulation for Playboy, Aldous was writing the same for Esquire. While Julian was broadcasting on the BBC, Aldous was speaking to ABC on population and world resources. Both used the widely recognised formula of “death control without birth control”. That is, the easily comprehensible idea that the public health control of infectious disease had been implemented across the world with incredible success especially in the reduction of infant mortality, but without any accompanying programs for birth control. The “balance is out”, as Aldous put it.

In the post-war world, there were a range of reasons for being troubled by world population growth. One was geopolitical, especially as the Cold War unfolded, when population control policies were associated with US-led anti-communism. A higher standard of living, linked to fertility control in then-named third-world economies, was understood to offset hunger and thus political discontent. For the White House, population planning was about ensuring food security and keeping polities this side, not that side, of a communist line. For leaders of newly independent nation-states, not least Jawaharlal Nehru in India, lower fertility rates meant higher standards of living and economic “development”. For any number of economists, lowering fertility rates was a means of averting future wars. For Aldous Huxley, population control was a road to world peace.

For Julian, however, his desire to manage human fertility was largely driven by early environmentalist politics. He sought to save wildlife habitats from encroaching cultivation, all those additional acres turned to the plough to provide grain for ever-growing numbers of humans. He was also driven by a feminist politics of sorts. He argued his whole life that reliable birth control should be available to all women, not just some, and that there was little human freedom for women bearing eight, nine, 10 children out of their worn-out bodies. The good and the bad of population control and family-planning history is well known. Yet we need to recall how recent and unprecedented in human history effective contraception actually is. Julian knew it. His generation and milieu often considered birth control one of the great technological developments of humankind, as significant in the long history of human affairs, he would say, as fire, printing, or electricity: “In time it will change the entire course of history.” It has.

It is sobering to observe how much more sensitive the Huxleys were to the gender dynamics of population policy than Musk and his ilk today. Women around the world are now opting en masse to have fewer children, and to do so later in life. The reasons are multiple: women are marrying later, retaining employment, getting educated, and accessing contraception. But collectively, this is one of the truly phenomenal changes of modern world history. In the UK, for example, the birth rate fell from 5.63 births per woman in the Huxleys’ grandfather’s time to 1.753 in our own. In India, it fell from at least 6.0 to 2.2 births per woman. But if the pro-natalists had their way, and this global trend towards lower fertility were to be reversed, it would be women bearing the brunt of it. And that would be impossible to justify.

As the planet approaches eight billion, the change in fertility rate since the Huxleys’ time means we need not be alarmed, as they were, by global “overpopulation”. Nor should we worry about an incorrectly named global “depopulation”. What we really need to be alarmed by are crude rationalisations for women to breed more. There lie the truly sinister lessons of history.