SUNDAY, APR 11, 2020: NOTE TO FILE

The Bottleneck

From The Future of Life by E.O. Wilson 2003

TOPICS: ECONOMISTS, FROM THE WIRES, ENVIRONMENTALISTS

The pattern of human population growth in the 20th century was more bacterial than primate. —E.O. Wilson

Abstract: The Bottleneck chapter from E.O. Wilson's The Future of Life includes a look at 'the economist' and 'the environmentalist' as players. While these two polar views of the economic future contend, Wilson doesn't wish to imply the existence of two cultures with distinct ethos. The economist is part of M. King Hubbert's 'monetary culture' (as champion of), and so is the environmentalist (who has served by stopping rivers from catching on fire and controlling visual and olfactory air pollution...). Even when Tweedledee and Tweedledum agree to have a battle, both fight for the good of humanity and the biosphere (ask them). Contention happens when nice new rattles are spoiled or other self interests/causes are frustrated. Meanwhile the pace of planetary destruction has not slowed. There actually are, as C.P. Snow and others have noted, two subcultures within modern techno-industrial society. There is the monetary culture worldview and the 'matter-energy systems' worldview as Hubbert called the other one. These are distinct as one is humancentric (anthropocentric) and the other naturcentric (ecocentric). They are not bedfellows (though most scientists and ecologists, like other humans, can compartmentalize), and while some scientists are environmentalists, they do not thereby serve the matter-energy systems worldview. For about 300 years, in the West's monetary culture (now global), the economist's narratives have dominated those who believe they have dominion over Nature (I estimate about 7k worldwide get a PhD in neoclassical economics each year to serve the socico-politio-economic system). No complex society has been dominated by the matter-energy systems worldview that environmentalists pick and choose from but do not think in terms of, as most other specialists do not. Yet.

TUCSON (A-P) — Within the domain of science, of what-is inquiry, what place is there for beliefs, including deeply held ones? What about political ones? Postmodern ones? Metamodern or ecomodern ones? Does life have intrinsic value? Do humans differ in kind from other animals? Short non-belief-based answer: no. Who assigns 'intrinsic' value? Who paints legs on a snake? That Nature and humans can be valued and that humans do differ (e.g. in the complexity of their verbal behavior) is evident, but stand down and imply no more. Claim that life can be valued by humans and cabbages differ from humans. Is hemoglobin superior to chlorophyll? What is the future of life? Of human life? I don't know, but E.O. Wilson knows enough to have an opinion.

Chapter 2

The twentieth century was a time of exponential scientific and technical advance, the freeing of the arts by an exuberant modernism, and the spread of democracy and human rights throughout the world. It was also a dark and savage age of world wars, genocide, and totalitarian ideologies that came dangerously close to global domination. While preoccupied with all this tumult, humanity managed collaterally to decimate the natural environment and draw down the nonrenewable resources of the planet with cheerful abandon. We thereby accelerated the erasure of entire ecosystems and the extinction of thousands of million-year-old species. If Earth's ability to support our growth is finite —and it is— we were mostly too busy to notice.

As a new century begins, we have begun to awaken from this delirium. Now, increasingly postideological in temper, we may be ready to settle down before we wreck the planet. It is time to sort out Earth and calculate what it will take to provide a satisfying and sustainable life for everyone into the indefinite future. The question of the century is: How best can we shift to a culture of permanence, both for ourselves and for the biosphere that sustains us?

The bottom line is different from that generally assumed by our leading economists and public philosophers. They have mostly ignored the numbers that count. Consider that with the global population past six billion and on its way to eight billion or more by midcentury, per capita freshwater and arable land are descending to levels resource experts agree are risky. The ecological footprint —the average amount of productive land and shallow sea appropriated by each person in bits and pieces from around the world for food, water, housing, energy, transportation, commerce, and waste absorption— is about one hectare (2.5 acres) in developing nations but about 9.6 hectares (24 acres) in the U.S. The footprint for the total human population is 2.1 hectares (5.2 acres). For every person in the world to reach present U.S. levels of consumption with existing technology would require four more planet Earth's. The five billion people of the developing countries may never wish to attain this level of profligacy. But in trying to achieve at least a decent standard of living, they have joined the industrial world in erasing the last of the natural environments. At the same time, Homo sapiens has become a geophysical force, the first species in the history of the planet to attain that dubious distinction. We have driven atmospheric carbon dioxide to the highest levels in at least 200,000 years, unbalanced the nitrogen cycle, and contributed to a global warming that will ultimately be bad news everywhere. For every person in the world to reach present U.S. levels of consumption with existing technology would require four more planet Earth's.

In short, we have entered the Century of the Environment, in which the immediate future is usefully conceived as a bottleneck. Science and technology, combined with a lack of self-understanding and a Paleolithic obstinacy, brought us to where we are today. Now science and technology, combined with foresight and moral courage, must see us through the bottleneck and out.

'Wait! Hold on there just one minute!'

That is the voice of the cornucopian economist. Let us listen to him carefully. He is focused on production and consumption. These are what the world wants and needs, he says. He is right, of course. Every species lives on production and consumption. The tree finds and consumes nutrients and sunlight; the leopard finds and consumes the deer. And the farmer clears both away to find space and raise corn —for consumption. The economist's thinking is based on precise models of rational choice and near-horizon timelines. His parameters are the gross domestic product, trade balance, and competitive index. He sits on corporate boards, travels to Washington, occasionally appears on television talk shows. The planet, he insists, is perpetually fruitful and still underutilized.

The ecologist has a different worldview. He is focused on unsustainable crop yields, overdrawn aquifers, and threatened ecosystems. His voice is also heard, albeit faintly, in high government and corporate circles. He sits on nonprofit foundation boards, writes for Scientific American, and is sometimes called to Washington. The planet, he insists, is exhausted and in trouble.

The Economist

'Ease up. In spite of two centuries of doomsaying, humanity is enjoying unprecedented prosperity. There are environmental problems, certainly, but they can be solved. Think of them as the detritus of progress, to be cleared away. The global economic picture is favorable. The gross national products of the industrial countries continue to rise. Despite their recessions, the Asian tigers are catching up with North America and Europe. Around the world, manufacture and the service economy are growing geometrically. Since 1950 per capita income and meat production have risen continuously. Even though the world population has increased at an explosive 1.8 percent each year during the same period, cereal production, the source of more than half the food calories of the poorer nations and the traditional proxy of worldwide crop yield, has more than kept pace, rising from 275 kilograms per head in the early 1950s to 370 kilograms by the 1980s. The forests of the developed countries are now regenerating as fast as they are being cleared, or nearly so. And while fibers are also declining steeply in most of the rest of the world —a serious problem, I grant— no global scarcities are expected in the foreseeable future. Agriforestry has been summoned to the rescue: more than 20 percent of industrial wood fiber now comes from tree plantations.

'Social progress is running parallel to economic growth. Literacy rates are climbing, and with them the liberation and empowerment of women. Democracy, the gold standard of governance, is spreading country by country. The communication revolution powered by the computer and the Internet has accelerated the globalization of trade and the evolution of a more irenic international culture.

'For two centuries the specter of Malthus troubled the dreams of futurists. By rising exponentially, the doomsayers claimed, population must outstrip the limited resources of the world and bring about famine, chaos, and war. On occasion this scenario did unfold locally. But that has been more the result of political mismanagement than Malthusian mathematics. Human ingenuity has always found a way to accommodate rising populations and allow most to prosper. The green revolution, which dramatically raised crop yields in the developing countries, is the outstanding example. It can be repeated with new technology. Why should we doubt that human entrepreneurship can keep of on an upward-turning curve?

'Genius and effort have transformed the environment to the benefit of human life. We have turned a wild and inhospitable world into a garden. Human dominance is Earth's destiny. The harmful perturbations we have caused can be moderated and reversed as we go along.'

The Environmentalist

'Yes, it's true that the human condition has improved dramatically in many ways. But you've painted only half the picture, and with all due respect the logic it uses is just plain dangerous. As your worldview implies, humanity has learned how to create an economy-driven paradise. Yes again —but only on an infinitely large and malleable planet. It should be obvious to you that Earth is finite and its environment increasingly brittle. No one should look to gross national products and corporate annual reports for a competent projection of the world's long-term economic future. To the information there, if we are to understand the real world, must be added the research reports of natural-resource specialists and ecological economists. They are the experts who seek an accurate balance sheet, one that includes a full accounting of the costs to the planet incurred by economic growth.

'This new breed of analysts argues that we can no longer afford to ignore the dependency of the economy and social progress on the environmental resource base. It is the content of economic growth, with natural resources factored in, that counts in the long term, not just the yield in products and currency. A country that levels its forests, drains its aquifers, and washes its topsoil downriver without measuring the cost is a country traveling blind. It faces a shaky economic future. It suffers the same delusion as the one that destroyed the whaling industry. As harvesting and processing techniques were improved, the annual catch of whales rose, and the industry flurished. But the whale populations declined in equal measure until they were depleted. Several species, including the blue whale, the largest animal species in the history of Earth, came close to extinction. Whereupon most whaling was called to a hault. Extend that arguement to falling ground water, drying rivers, and shrinking per-capita arable land, and you get the picture.

'Suppose that the conventionally measured global economic output, now at about $31 trillion, were to expand at a healthy 3 percent annually. By 2050 it would in theory reach $138 trillion. With only a small leveling adjustment of this income, the entire world population would be prosperous by current standards. Utopia at last, it would seem! What is the flaw in the argument? It is the environment crumbling beneath us. If natural resources, particularly freshwater and arable land, continue to diminish at their present per capita rate, the economic boom will lose steam, in the course of which —and this worries me even if it doesn't worry you —the effort to enlarge productive land will wipe out a large part of the world's fauna and flora.

'The appropriation of productive land--the ecological footprint —is already too large for the planet to sustain, and it's growing larger. A recent study building on this concept estimated that the human population exceeded Earth's sustainable capacity around the year 1978. By 2000 it had overshot by 1.4 times that capacity. If 12 percent of land were now to be set aside in order to protect the natural environment, as recommended in the 1987 Brundtland Report, Earth's sustainable capacity will have been exceeded still earlier, around 1972. In short, Earth has lost its ability to regenerate —unless global consumption is reduced or global production is increased, or both.'

- - - - -

By dramatizing these two polar views of the economic future, I don't wish to imply the existence of two cultures with distinct ethos. All who care about both the economy and environment, and that includes the vast majority, are members of the same culture. The gaze of our two debaters is fixed on different points in the space-time scale in which we all dwell. They differ in the factors they take into account in forecasting the state of the world, how far they look into the future, and how much they care about nonhuman life. Most economists today, and all but the most politically conservative of their public interpreters, recognize very well that the world has limits and that the human population cannot afford to grow much larger. They know that humanity is destroying biodiversity. They just don't like to spend a lot of time thinking about it.

The environmentalist view is fortunately spreading. Perhaps the time has come to cease calling it the 'environmentalist' view, as though it were a lobbying effort outside the mainstream of human activity, and to start calling it the real-world view. In a realistically reported and managed economy, balanced accounting will be routine. The conventional gross national product (GNP) will be replaced by the more comprehensive genuine progress indicator (GPI), which includes estimates of environmental costs of economic activity. Already a growing number of economists, scientists, political leaders, and others have endorsed precisely this change.

What, then, are essential facts about population and environment? From existing databases we can answer that question and visualize more clearly the bottleneck through which humanity and the rest of life are now passing.

On or about October 12, 1999, the world population reached six billion. It has continued to climb at an annual rate of 1.4 percent, adding 200,000 people each day or the equivalent of the population of a large city each week. The rate, though beginning to slow, is still basically exponential: the more people, the faster the growth, thence still more people sooner and an even faster growth, and so on upward toward astronomical numbers unless the trend is reversed and growth rate is reduced to zero or less. This exponentiation means that people born in 1950 were the first to see the human population double in their lifetime, from 2.5 billion to over six billion now. During the 20th century more people were added to the world than in all of previous human history. In 1800 there had been about one billion and in 1900, still only 1.6 billion.

The pattern of human population growth in the 20th century was more bacterial than primate. When Homo sapiens passed the six-billion mark we had already exceeded by perhaps as much as 100 times the biomass of any large animal species that ever existed on the land. We and the rest of life cannot afford another 100 years like that.

By the end of the century some relief was in sight. In most parts of the world —North and South America, Europe, Australia, and most of Asia— people had begun gingerly to tap the brake pedal. The worldwide average number of children per woman fell from 4.3 in 1960 to 2.6 in 2000. The number required to attain zero population growth— that is, the number that balances the birth and death rates and holds the standing population size constant— is 2.1 (the extra one tenth compensates for infant and child mortality). When the number of children per woman stays above 2.1 even slightly, the population still expands exponentially. This means that although the population climbs less and less steeply as the number approaches 2.1, humanity will still, in theory, eventually come to weigh as much as Earth and, if given enough time, will exceed the mass of the visible universe. This fantasy is a mathematician's way of saying that anything above zero population growth cannot be sustained. If, on the other hand, the average number of children drops below 2.1, the population enters negative exponential growth and starts to decline. To speak of 2.1 in exact terms as the breakpoint is of course an oversimplification. Advances in medicine and public health can lower the breakpoint toward the minimal, perfect number of 2.0 (no infant or childhood deaths), while famine, epidemics, and war, by boosting mortality, can raise it well above 2.1. But worldwide, over an extended period of time, local differences and statistical fluctuations wash one another out and the iron demographic laws grind on. They transmit to us always the same essential message, that to breed in excess is to overload the planet.

By 2000 the replacement rate in all of the countries of western Europe had dropped below 2.1. The lead was taken by Italy, at 1.2 children per woman (so much for the power of natalist religious doctrine). Thailand also passed the magic number, as well as the nonimmigrant population of the U.S.

When a country descends to its zero-population birth rates or even well below, it does not cease absolute population growth immediately, because the positive growth experienced just before the breakpoint has generated a disproportionate number of young people with most of their fertile years and life ahead of them. As this cohort ages, the proportion of child-bearing people diminishes, the age distribution stabilizes at the zero-population level, the slack is taken up, and population growth ceases. Similarly, when a country dips below the breakpoint, a lag period intervenes before the absolute growth rate goes negative and the population actually declines. Italy and Germany, for example, have entered a period of such true, absolute negative population growth.

The decline in global population growth is attributable to three interlocking social forces: the globalization of an economy driven by science and technology, the consequent implosion of rural populations into cities, and, as a result of globalization and urban implosion, the empowerment of women. The freeing of women socially and economically results in fewer children. Reduced reproduction by female choice can be thought a fortunate, indeed almost miraculous, gift of human nature to future generations. It could have gone the other way: women, more prosperous and less shackled, could have chosen the satisfactions of a larger brood. They did the opposite. They opted for a smaller number of quality children, who can be raised with better health and education, over a larger family.

They simultaneously chose better, more secure lives for themselves. The tendency appears to be very widespread, if not universal. Its importance cannot be overstated. Social commentators often remark that humanity is endangered by its own instincts, such as tribalism, aggression, and personal greed. Demographers of the future will, I believe, point out that on the other hand humanity was saved by this one quirk in the maternal instinct.

The global trend toward smaller families, if it continues, will eventually halt population growth and afterward reverse it. What will be the peak, and when will it occur? And how will the environment fare as humanity climbs to the peak? In September 1999, the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs released a spread of projections to the year 2050 bases on four possible scenarios of female fertility. If the number of children dropped to two per woman immediately—in other words, beginning in 2000—the world population would be on its way to leveling off by aournd 2050 to approximately 7.3 billion. This degree of descent has not happened of course and is unlikely to be attained for at least several more decades. Thus, 7.3 billion, is improbably low. If, at the other extreme, fertility continues to fall at the current rate, the population will reach 10.7 billion by 2050 and continue steeply upwards for a few more decades before peaking. If it holds to the present growth rate, it will reach 14.4 billion by 2050. Finally, if fertility fall more rapidly than the present rate, on its way to a global 2.1 and below, the population will reach 8.9 billion by 2050; in this case also it will continue to climb for a while longer, but less steeply so. This final scenario seems to be the most likely of the trends. Very broadly, then, it seems probable that the world population will peak in the late twenty-first century somewhere between 9 and 10 billion. If population control efforts are inensified, the number can be broght closer to 9 than to 10 billion.

Enough slack still exists in the system to justify guarded optimism. Women given a choice and affordable contraceptive methods generally practice birth control. The percentage who do so still varies enormously among countries. Europe and the United States, for example, have topped 70 percent; Thailand and Columbia are closing in on that figure. Indonesia is up to about 50 percent; Bangledish and Kenya have passed 30 percent; but Pakistan hold with little change at around 10 percent. The stated intention, or at least the acquiescence, of national governments favors a continued rise in the levels of birth control worldwide. By 1996 about 130 countries subsidized family-planning services. More than half of all developing countries in particular also had official population policies to accompany their economic and military policies, and more than 90 percent of the rest stated their intention to follow suit. The U.S., where the idea is still virtually taboo, remained a stunning exception.

The encouragement of population control by developing countries comes not a moment too soon. The environmental fate of the world lies ultimately in their hands. They now account for virtually all global population growth, and their drive toward higher per capita consumption will be relentless.

The consequences of their reproductive prowess are multiple and deep. The people of the developing countries are already far younger than those in the industrial countries and destined to become more so. The streets of Lagos, Manaus, Karachi, and other cities in the developing world are a sea of children. To an observer fresh from Europe or North America, the crowds give the feel of a gigantic school just let out. In at least 68 of the countries, more than 40 percent of the population is under 15 years of age.

A country poor to start with and composed largely of young children and adolescents is strained to provide even minimal health services and education for its people. Its superabundance of cheap, unskilled labor can be turned to some economic advantage but unfortunately also provides cannon fodder for ethnic strife and war. As the populations continue to explode and water and arable land grow scarcer, the industrial countries will feel their pressure in the form of many more desperate immigrants and the risk of spreading international terrorism. I have come to understand the advice given me many years ago when I argued the case for the natural environment to the president's scientific adviser: your patron is foreign policy.

Stretched to the limit of its capacity, how many people can the planet support? A rough answer is possible, but it is a sliding one contingent on three conditions: how far into the future the planetary support is expected to last, how evenly the resources are to be distributed, and the quality of life most of humanity expects to achieve. Consider food, which economists commonly use as a proxy of carrying capacity. The current world production of grains, which provide most of humanity's calories, is about 2 billion tons annually. That is enough, in theory, to feed 10 billion East Indians, who eat primarily grains and very little meat by Western standards. But the same amount can support only about 2.5 billion Americans, who convert a large part of their grains into livestock and poultry. The ability of India and other developing countries is problematic. If soil erosion and ground water withdrawal continue at there present rates until the world population reaches (and hopefully peaks) at 9 to 10 billion, shortages of food seem inevitable. There are two ways to stop short of the wall. Either the industrialized populations move down the food chain to a more vegetarian diet, or the agricultural yield of productive land worldwide is increased by more than 50 percent.

The constraints of the biosphere are fixed. The bottleneck through which we are passing is real. It should be obvious to anyone not in a euphoric delirium that whatever humanity does or does not do, Earth's capacity to support our species is approaching the limit. We already appropriate by some means or other 40 percent of the planet's organic matter produced by green plants. If everyone agreed to become vegetarian, leaving little or nothing for livestock, the present 1.4 billion hectares of arable land (3.5 billion acres) would support about 10 billion people. If humans utilized as food all of the energy captured by plant photosynthesis on land and sea, some 40 trillion watts, the planet could support about 17 billion people. But long before that ultimate limit was approached, the planet would surely have become a hellish place to exist. There may, of course, be escape hatches. Petroleum reserves might be converted into food, until they are exhausted. Fusion energy could conceivably be used to create light, whose energy would power photosynthesis, ramp up plant growth beyond that dependent on solar energy, and hence create more food. Humanity might even consider becoming someday what the astrobiologists call a type II civilization and harness all the power of the sun to support human life on Earth and on colonies on and around the other solar planets. (No intelligent life forms in the Milky Way galaxy are likely at this level; otherwise they would probably have been already detected by the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI, programs.) Surely these are not frontiers we will wish to explore in order simply to continue our reproductive folly.

The epicenter of environmental change, the paradigm of population stress, is the People's Republic of China. By 2000 its population was 1.2 billion, one fifth of the world total. It is thought likely by demographers to creep up to 1.6 billion by 2030. During 1950-2000 China's people grew by 700 million, more than existed in the entire world at the start of the industrial revolution. The great bulk of this increase is crammed into the basins of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers, covering an area about equal to that of the eastern U.S. Hemmed in to the west by deserts and mountains, limited to the south by resistance from other civilizations, their agricultural populations simply grew denser on the land their ancestors had farmed for millennia. China became in effect a great overcrowded island, a Jamaica or Haiti writ large.

Highly intelligent and innovative, its people have made the most of it. Today China and the U.S. are the two leading grain producers of the world. But China's huge population is on the verge of consuming more than it can produce. In 1997 a team of scientists, reporting to the U.S. National Intelligence Council (NIC), predicted that China will need to import 175 million tons of grain annually by 2025. Extrapolated to 2030, the annual level is 200 million tons —the entire amount of grain exported annually in the world at the present time. A tick in the parameters of the model could move these figures up or down, but optimism would be a dangerous attitude in planning strategy when the stakes are so high. After 1997 the Chinese in fact instituted a province-level crash program to boost grain level to export capacity. The effort was successful but may be short-lived, a fact the government itself recognizes. It requires cultivation of marginal land, higher per acre environmental damage, and a more rapid depletion of the country's precious groundwater.

According to the NIC report, any slack in China's production may be picked up by the Big Five grain exporters: the U.S., Canada, Argentina, Australia, and the European Union. But the exports of these dominant producers, after climbing steeply in the 1960s and 1970s, tapered off to near their present level in 1980. With existing agricultural capacity and technology, this output does not seem likely to increase to any significant degree. The U.S. and the European Union have already returned to production all of the cropland idled under earlier farm commodity programs. Australia and Canada, largely dependent on dryland farming, are constrained by low rainfall. Argentina has the potential to expand, but due to its small size, the surplus it produces is unlikely to exceed 10 million tons of grain production per year.

China relies heavily on irrigation, with water drawn from its aquifers and great rivers. The greatest impediment is again geographic: two thirds of China's agriculture is in the north, but four fifths of the water supply is in the south —that is, principally in the Yangtze River Basin. Irrigation and withdrawals for domestic and industrial use have depleted the northern basins, from which flow the waters of the Yellow, Hai, Huai, and Liao rivers. Added to the Yangtze Basin, these regions produce three-fourths of China's food and support 900 million of its population. Starting in 1972, the Yellow River Channel has gone bone dry almost yearly through part of its course in Shandong Province, as far inland as the capital, Jinan, thence down all the way to the sea. In 1997 the river stopped flowing for 130 days, then restarted and stopped again through the year for a record total of 226 dry days. Because Shandong Province normally produces a fifth of China's wheat and a seventh of its corn, the failure of the Yellow River is of no little consequence. The crop losses in 1997 alone reached $1.7 billion.

Meanwhile the groundwater of the northern plains has dropped precipitously, reaching an average rate of 1.5 meters (five feet) per year by the mid-1990s. Between 1965 and 1995 the water table fell 37 meters (121 feet) beneath Beijing itself.

Faced with chronic water shortages in the Yellow River Basin, the Chinese government has undertaken the building of the Xiaolangdi Dam, which will be exceeded in size only by the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. The Xiaolangdi is expected to solve the problems of both periodic flooding and drought. Plans are being laid in addition for the construction of canals to siphon water from the Yangtze, which never grows dry, to the Yellow River and Beijing, respectively.

These measures may or may not suffice to maintain Chinese agriculture and economic growth. But they are complicated by formidable side effects. Foremost is silting from the upriver loess plains, which makes the Yellow River the most turbid in the world and threatens to fill the Xiaolangdi Reservoir, according to one study, as soon as 30 years after its completion.

China has maneuvered itself into a position that forces it continually to design and redesign its lowland territories as one gigantic hydraulic system. But this is not the fundamental problem. The fundamental problem is that China has too many people. In addition, its people are admirably industrious and fiercely upwardly mobile. As a result, their water requirements, already oppressively high, are rising steeply. By 2030 residential demands alone are projected to increase more than fourfold, to 134 billion tons, and industrial demands fivefold, to 269 billion tons. The effects will be direct and powerful. Of China's 617 cities, 300 already face water shortages.

The pressure on agriculture is intensified in China by a dilemma shared in varying degrees by every country. As industrialization proceeds, per capita income rises, and the populace consumes more food. They also migrate up the energy pyramid to meat and dairy products. Because fewer calories per kilogram of grain are obtained when first passed through poultry and livestock instead of being eaten directly, per capita grain consumption rises still more. All the while the available water supply remains static or nearly so. In an open market, the agricultural use of water is outcompeted by industrial use. A thousand tons of freshwater yields a ton of wheat, worth $200, but the same amount of water in industry yields $14,000. As China, already short on water and arable land, grows more prosperous through industrialization and trade, water becomes more expensive. The cost of agriculture rises correspondingly, and unless the collection of water is subsidized, the price of food also rises. This is in part the rationale for the great dams at Three Gorges and Xiaolangdi, built at enormous public expense.

In theory, an affluent industrialized country does not have to be agriculturally independent. In theory, China can make up its grain shortage by purchasing from the Big Five grain-surplus nations. Unfortunately, its population is too large and the world surplus too restrictive for it to solve its problem without altering the world market. All by itself, China seems destined to drive up the price of grain and make it harder for the poorer developing countries to meet their own needs. At the present time, grain prices are falling, but this seems certain to change as the world population soars to nine billion or beyond.

The problem, resource experts agree, cannot be solved entirely by hydrological engineering. It must include shifts from grain to fruit and vegetables, which are more labor-intensive, giving China a competitive edge. To this can be added strict water conservation measures in industrial and domestic use; the use of sprinkler and drip irrigation in cultivation, as opposed to the traditional and more wasteful methods of flood and furrow irrigation; and private land ownership, with subsidies and price liberalization, to increase conservation incentives for farmers.

Meanwhile the surtax levied on the environment to support China's growth, though rarely entered on the national balance sheets, is escalating to a ruinous level. Among the most telling indicators is the pollution of water. Here is a measure worth pondering. China has in all 50,000 kilometers of major rivers. Of these, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, 80 percent no longer support fish. The Yellow River is dead along much of its course, so fouled with chromium, cadmium, and other toxins from oil refineries, paper mills, and chemical plants as to be unfit for either human consumption or irrigation. Diseases from bacterial and toxic-waste pollution are epidemic.

China can probably feed itself to at least midcentury, but its own data show that it will be skirting the edge of disaster even as it accelerates its lifesaving shift to industrialization and megahydrological engineering. The extremity of China's condition makes it vulnerable to the wild cards of history. A war, internal political turmoil, extended droughts, or crop disease can kick the economy into a downspin. Its enormous population makes rescue by other countries impracticable.

China deserves close attention, not just as the unsteady giant whose missteps can rock the world, but also because it is so far advanced along the path to which the rest of humanity seems inexorably headed. If China solves its problems, the lessons learned can be applied elsewhere. That includes the U.S., whose citizens are working at a furious pace to overpopulate and exhaust their own land and water from sea to shining sea.

Environmentalism is still widely viewed, especially in the U.S., as a special-interest lobby. Its proponents, in this blinkered view, flutter their hands over pollution and threatened species, exaggerate their case, and press for industrial restraint and the protection of wild places, even at the cost of economic development and jobs.

Environmentalism is something more central and vastly more important. Its essence has been defined by science in the following way. Earth, unlike the other solar planets, is not in physical equilibrium. It depends on its living shell to create the special conditions on which life is sustainable. The soil, water, and atmosphere of its surface have evolved over hundreds of millions of years to their present condition by the activity of the biosphere, a stupendously complex layer of living creatures whose activities are locked together in precise but tenuous global cycles of energy and transformed organic matter. The biosphere creates our special world anew every day, every minute, and holds it in a unique, shimmering physical disequilibrium. On that disequilibrium the human species is in total thrall. When we alter the biosphere in any direction, we move the environment away from the delicate dance of biology. When we destroy ecosystems and extinguish species, we degrade the greatest heritage this planet has to offer and thereby threaten our own existence.

Humanity did not descend as angelic beings into this world. Nor are we aliens who colonized Earth. We evolved here, one among many species, across millions of years, and exist as one organic miracle linked to others. The natural environment we treat with such unnecessary ignorance and recklessness was our cradle and nursery, our school, and remains our one and only home. To its special conditions we are intimately adapted in every one of the bodily fibers and biochemical transactions that gives us life.

That is the essence of environmentalism. It is the guiding principle of those devoted to the health of the planet. But it is not yet a general worldview, evidently not yet compelling enough to distract many people away from the primal diversions of sport, politics, religion, and private wealth.

The relative indifference to the environment springs, I believe, from deep within human nature. The human brain evidently evolved to commit itself emotionally only to a small piece of geography, a limited band of kinsmen, and two or three generations into the future. To look neither far ahead nor far afield is elemental in a Darwinian sense. We are innately inclined to ignore any distant possibility not yet requiring examination. It is, people say, just good common sense. Why do they think in this shortsighted way? The reason is simple: it is a hardwired part of our Paleolithic heritage. For hundreds of millennia, those who worked for short-term gain within a small circle of relatives and friends lived longer and left more offspring —even when their collective striving caused their chiefdoms and empires to crumble around them. The long view that might have saved their distant descendants required a vision and extended altruism instinctively difficult to marshal.

The great dilemma of environmental reasoning stems from this conflict between short-term and long-term values. To select values for the near future of one's own tribe or country is relatively easy. To select values for the distant future of the whole planet also is relatively easy--in theory, at least. To combine the two visions to create a universal environmental ethic is, on the other hand, very difficult. But combine them we must, because a universal environmental ethic is the only guide by which humanity and the rest of life can be safely conducted through the bottleneck into which our species has foolishly blundered.

Hubbert would beg to differ as he clearly saw that 'industrial civilization is handicapped by the coexistence of two universal, overlapping, and incompatible intellectual systems: the accumulated knowledge of the last four centuries of the properties and interrelationships of matter and energy [the systems worldview]; and the associated monetary culture which has evolved from folkways of prehistoric origin' (ref). The two sides (economist/environmentalist) of the same coin (industrial society) could each stand down and cooperate, but then what? The humancentric monetary culture would be united to select for its own, albate more environmental, failure. As the two cultures are incompatible (monetary vs systems), the one currently in power and running the show needs to stand down (embrace system over self) or, perhaps far more likely, go down, which is what everyone who is an Anthropocene enthusiast is unintentionally working towards.

The idea of disagreeing, in however minor a manner, with E.O. Wilson borders on the unthinkable, but I sometimes think up to six unthinkable thoughts before breakfast.

'Environmentalism is still widely viewed, especially in the U.S., as a special-interest lobby. Its proponents.., press for industrial restraint and the protection of wild places, even at the cost of economic development and jobs.'

'Environmentalism is something more central and vastly more important...', and the rest of his claims are evident as usual.

In the first usage of 'environmentalism' I have no issues, no red flags appear, but the second seems to want to make of environmentalism something Wilson would want it to be but is not and perhaps cannot be. To say 'environmentalism should be something...' it isn't would be to sing sweetly, so perhaps I overreact to the implications of 'is'. That there is a need, one might say an existential need, for 'something more central and vastly more important' is not a thought I can disagree with in the least. I would not, however, call it environmentalism (naturocracy would be vastly different). Are environmentalists part of the problem or are they the best (or even only) hope for real solutions? Opinion should vary as that they are part of the problem should be thinkable and of concern to all environmental activists and their supporters.

I was nine-years old when Rachel Carson published Silent Spring and concerned citizens began to largely self-organize to form an environmental movement that was a fixture of my coming of age, one that climaxed when 1 percent of Americans 'took to the streets' in some form of protest/activity on the first Earth Day in 1970, vastly larger than XR has managed. As the years went by fewer rivers caught fire and city air seemed noticeably more breathable, but the pace of planetary destruction was not noticeably slowed. Some Anthropocene enthusiasts developed different recreational sex, drugs, and musical preferences, but there was no cultural revolution, as much as I thought there should be.

Environmentalism became a thing. Some were for it, some against, which was politically acceptable, well within the collective Overton window so environmental policies proliferated. In 1964 a Wilderness Preservation Act was passed in the USA that called the few remaining roadless areas 'wilderness' (some contained abandoned roads and even a few included roads used by recreational off-roaders that were closed despite the heart-felt protests, but many miles almost beyond the dreams of avarice remained for their use). But the areas were roadless because they contained no resources of enough value to build or maintain roads into, so in effect, except for grazing, hunting/fishing, trapping, and recreational mining (all permitted uses per the Wilderness Preservation Act), the areas became what they already were. Many politicians and environmentalists were seen nodding, winking and grinning broadly.

Whole branches of governance arose to manage environmental policies and universities provided the policy and decision makers. Environmentalists mitigated the damage of Growth's Mandate, and thereby made the development of Earth (destruction of the planetary life-support system) go as well as it could for humans in the short-term. More National Parks (recreational areas for humans) were formed and wilderness areas declared to exist. People felt better. When sustainability concerns arose, Schools of Sustainability formed at universities worldwide and grew exponentially in number to supply specialists who would ensure that development was sustainable (somehow). Meanwhile, the pace of planetary destruction has not slowed. The rise of environmentalism managed to allow humans to prosper in the short-term, and CFCs and DDT were replaced by other chemicals for better living (for humans), but meanwhile.....

In 1971 I took my first college biology class and, despite biology (of all sciences) being my forte, I would have flunked the class if I had not withdrawn. The professor was an enthusiast with no apparent interest in the study of life. He was a strong supporter of the environmental movement and sought to lead students into becoming environmentally aware. He was actually an environmentalist (i.e. not a scientist) who, when not distracted by talking about textbook biology, offered every environmentalist talking point for consideration. Of course he grew and ate only organic foods and by making environmentally responsible consumer choices and recycling, his weekly trash amounted to one bag. Today he likely talks of the evils of plastic straws and carries a stainless steel straw with him in a bamboo case at all times, still endeavoring to save the world just as I hope to. I merely have different ideas about what might work (and becoming an environmentalist isn't one of them). His deeply held beliefs and causes were perhaps as admirable as he thought they were, but it all had nothing to do with the study of life on Earth apart from human ecology in terms of social constructs.

In the same year I chanced to see a book on the new books display in the college library that, in hindsight, made me the worthless misfit I am today. It was Environment, Power, and Society by Howard T. Odum. My neural net was repatterned by Odum's 'better view'. I sensed this was no ordinary book and that perhaps Odum was no ordinary genius. Despite being a poor student, I went to the bookstore and had them order me a copy. H.T. Odum was a systems ecologist, but not an environmentalist. He did not see them as trafficking in real solutions nor politically unsellable ideas (e.g. reality-based understanding of complex systems) such as descent, however prosperous (adaptive) we could manage to make it. Like Galileo he tried to get others to look through his macroscope of systems thinking, but few would. No environmentalists could look through it and see what they wanted to.

Neoclassical economists and environmentalists are not of two cultures. They are two sides of the same coin of the realm. Today's enthusiasts keep on keeping on. Some seek to keep on keeping on by doing what has worked for the last 300 years. Economists believe in business-as-usual (BAU) because it works (for a time). Environmentalists, like Lester Brown, demand change. Dietz and O'Neill seem to think we can transition to a steady-state economy about fourty or fifty years after we maybe could have. Progress must be based on renewable energy and not on fossil fuels, the more progressive types seem to think. We need a Green New Deal (GND) to keep on keeping on. But some say degrowth will be better than growth and we will transition, resiliently of course. If BAU is the wolf, then GND is the wolf in sheep's clothing. They are not of two cultures.

But there are two cultures within industrial society. As M. King Hubbert noted, there is the 'monetary culture' we are all a product of, and there is another having a foundationally different worldview: Call it what you will, but I'll go with Hubbert's 'matter-energy systems' worldview. Boiled down, one is humancentric (anthropocentric) and the other is naturcentric (ecocentric). The narratives of one are determined by preference and there are many. The narratives of the other are determined by Nature, who confirms or disconfirms hypotheses when asked in the proper way by those intent of listening. One lacks any way, apart from war/conflict/conquest, to confirm or disconfirm narratives. The other iterates, slowly at great effort with great care, towards one story of life, the universe, and everything. Some believe only in the ignorance of experts and others have an enthusiasm for authority, whether that of the indigenous or professors of environmental or sustainability studies. But the story of hu-mans standing down isn't to the liking of Anthropocene enthusiasts (so far as I know E.O. Wilson, in Half Earth, is the origin of this meme I've not seen used elsewhere), so they ignore, obfuscate, or deny it. The two cultures are incompatible, i.e. they cannot be bedfellows, one is not epistemologically part of the coin of the realm and, apart from services rendered, is an existential threat to the global empire which is a threat to the planetary life-support system all life on this pale blue dot depends on. The systems science literate have yet to seize the day or even write prescriptions for our continued evolution (e.g. design viable complex societies that might work).

The matter-energy systems worldview is tolerated by the dominant monetary culture for the 'milk and cheese and profit it brings' that is greatly (profitably) served by science and technology. Many fields of service are funded as specialties, served by many specialists, who are paid to serve the Growth Hegemon. Most professional scientists and technologists speak dialects (over 100) that few in other specialties understand. Systems science has the potential to unify all specialties and provide a common language (e.g. Hubbert's and Odum's 'better view'), a view through a macroscope, that connects all the dots created by the various conceptual microscopes.

But it hasn't happened yet. If it doesn't happen in the 21st century, the potential may be lost forever and a millennium. Failure to transition to thinking in systems (hu-mans standing down to transition from a human centered to a Nature centered worldview) could be the existential threat that prevents us from facing all others.

Hubbert was the instigator of Technocracy in the 1930s that would have been an expression of his matter-energy systems thinking if the Great Depression had had a biophysical basis. The first proposed technate was for North America, so those living elsewhere were discriminated against. Otherwise the only people who could not join were politicians and the currently politically active. Prior activists who had learned of the error, ignorance, and illusion of prior ways were allowed to be active within Technocracy. There is a coming bottleneck and there will be biophysical limits. As a rxevolutionary, I demand a new name for Hubbert's better worldview.

A few scientists who were paying attention (and thinking in systems) realized that 'Huston, we have an environmental crisis' in the early 1950s post the Great Acceleration, a far more concerning development than the Great Depression, but one almost no one, certainly no Anthropocene enthusiasts, wanted to slow down. David Suzuki was the only scientist to also be on TV week after week to tell humanity about the nature of things. In 1985 he offered his Planet for the Taking series.

In 1988 he interviewed over 150 scientists/experts from around the planet being taken and wrote an offering for radio. His It's a Matter of Survival series was the instigator for a massive (Canadian) public outpouring. Clear was 'that humans were destroying the very life-support systems of the planet on a grand scale, at an alarming rate.' Over 16,000 listeners wrote letters (pre-email) asking what they could do to turn things around before it was too late. He could only say, sorry, “I’m just the messenger,” and did, but Tara, his wife, said that wasn’t good enough, that it was time to talk about what to do. They started the David Suzuki Foundation in 1990. For decades the Foundation has endeavored away, some progress made, but — 'the pace of planetary destruction has not slowed' (per email he sent to those on the Foundation's email list (like me) on his 80th birthday, March 24, 2016). David, one the the top 10 (#5) most important Canadians to have ever lived, per Canadians, became the environmentalist extraordinaire, as being extraordinary was what he did.

David's message, that we are collectively heading full

speed ahead toward a wall, is common

knowledge among many scientists and students of

science, especially among those who are systems

literate, having an interest in Earth's systems science. A 50:50 chance of human extinction in the 21st century is not unthinkable .

David's message does not sell well, however, in the

oversold society of consumers without borders. It is not

possible to inquire into the nature of things without

thinking things that others will parse into political

terms. This allows them to reject anything claimed, no matter how evidence-based, as

political opinions are firmly held beliefs that demand

respect and to which everyone is entitled. If claims that are

based merely on reason and evidence differ from one's political views, then one merely has to see the claims as

politically motivated to dismiss them as false because you

firmly believe them to be false.

'People would rather believe than know.' ― E.O. Wilson

Force of Nature: The David Suzuki Movie won the People's Choice Documentary Award in 2010. Force of Nature looks at the events that shaped David Suzuki's life and career. The film weaves together scenes from the places and events that shaped Suzuki's life with a filming of his 'Last Lecture', which he describes as 'a distillation of my life and thoughts, my legacy, what I want to say before I die'.

David imagined the movie would be an epic eight-hour film with Avatar-like CGI to conjure up how humans live and could live in the ecosystems of the planet. 'We are the environment', he said as science, our tribal ancestors, and today's First Peoples (the few pre-agrarian ones left) agree. What he hoped would be a James Cameron-like film that might make a difference, turned into just a recap of the inconvenient truths he (Mr. Science) had mentioned before to standing ovations that amount to nothing insofar as our 'changing directions' or living as 'if we and the rest of life on Earth are to survive'.

The focus was too much on him and not what his finger has been pointing to for decades. It's an old story. Someone is enthusiastically pointing, 'Look, look! it's a finger pointing at the moon!' The evidence is that while many people, especially in Canada where he is an icon and household name, admire the icon (the way he speaks, but not so much the implications of what he says). Even those who have read his 52 books, like moths to a light, have difficulty transitioning to the no-bright-lights world to come. Such is the nature of things.

So, best guess: over 7 billion of Earth's 7.7+ billion humans are moth-like growthers (perfectly normal imperfect humans) who will continue to swam any detectable light [energy source] until only Sun, Moon and stars remain to shine upon an Earth that has been all used up. Virtually the only humans having a 'we are the environment' culture are those currently clinging to their vestigial pre-growther indigenous cultures. They will be at the forefront of the transition to come, not the upper-middle class, educated, environmentally sensitive consumers without borders who support the idea of transitioning (resiliently of course) and are enthusiastically ready to be oversold on sustainable development, services and products. Giving Suzuki a standing ovation or reading his books will not be enough. David may die still calling himself an environmentalist, but he will die as a man of science. He tried the environmentalist thing' meanwhile... I don't have to. Thank you David for doing so and explaining: The Fundamental Failure of Environmentalism, David Suzuki, which your Foundation removed from 'your' website. Science Matters even if blogs claiming that science matters do not.

To repeat, perhaps more

loudly for clarity, 'So, you're a stupid know-nothing eco-fascist from the hood who thinks humans are like moths?'

Yes: Humans and moths are both natural, normal animals. I am

absolutely, unequivocally saying that we human animals

who intend to live in complex societies should consider becoming unnatural and abnormal in living

our lives. Unlike moths and other animals, we have the

potential to do so. Flying into the light may feel good but involve existential concerns assuming a bit of 'foresight intelligence' (collectively unnatural so far) is used. Central to the 'ecolate view' or systems science view is to ask 'and then what?' which too few humans are asking.

To repeat, perhaps more

loudly for clarity, 'So, you're a stupid know-nothing eco-fascist from the hood who thinks humans are like moths?'

Yes: Humans and moths are both natural, normal animals. I am

absolutely, unequivocally saying that we human animals

who intend to live in complex societies should consider becoming unnatural and abnormal in living

our lives. Unlike moths and other animals, we have the

potential to do so. Flying into the light may feel good but involve existential concerns assuming a bit of 'foresight intelligence' (collectively unnatural so far) is used. Central to the 'ecolate view' or systems science view is to ask 'and then what?' which too few humans are asking.

It is as absolutely natural for humans to exploit opportunistic resources, pulsing even unto overshoot and collapse (or extinction), as it is for moths to be attracted to bright lights. Moths, lacking prior evolutionary experience with artificial lights, keep flying around and around, bashing themselves into them unto death. One can imagine a thoughtful moth asking why they were bashing themselves into a hot glowing piece of glass unto death. Her friends would say, 'because it feels good'. Human drug users give the same answer. Some 80% of Americans can no longer see the Milkyway at night from where they live due to the always on [for a time] glow and only 1% live in areas without light pollution.

Human power-and-speed addicts also think that consuming

the vat of planetary fossil fuels feels good (and it

does), and they firmly believe that if it feels good, that they should do it.

Again, perfectly natural and normal. In industrial areas

cars are the leading cause of death for humans over three years of age

(direct cause for aged 3 to 34 and indirect for those older secondary to

activity intolerance). In the US cars kill over 300 million vertebrates

and over 30 trillion invertebrates each year and more humans than guns

or all forms of violence, including legal, combined (excluding suicide).

The best of all possible worlds to come may involve finding a common ground between science and indigenous peoples who have retained some connectivity with nature and ability to live in it. Native land huggers provide love and knowing of this Earth and the things of it; science provides the understanding.

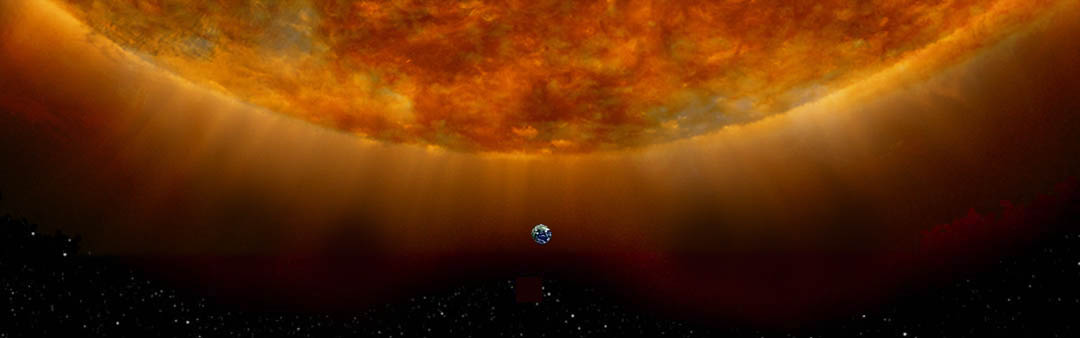

Human

exceptionalism is a core growther value.  The

history of science has been an unfolding of the

realization that humans are not the center about which the

universe spins nor even exempt from nature or natural laws

(nor protected by supernatural entities). We are star

stuff powered by a nearby star living in a thin film.

The

history of science has been an unfolding of the

realization that humans are not the center about which the

universe spins nor even exempt from nature or natural laws

(nor protected by supernatural entities). We are star

stuff powered by a nearby star living in a thin film.

First Peoples (pre-agrarian and agrarian Second Peoples) also have the potential to be attracted to artificial lights. The cultural values needed to live in nature and with nature has been selected for among those who were not able to dominate nature. We, who for a time (~300 years) have had dominion, need to adopt values our pre-growther ancestors learned the hard way and today's First Peoples can help teach us. This does not imply an uncritical endeavor to 'go native'. Tribal cultures have much to learn as well. For example, they demand Kennewich Man's 9,000 year old remains be given a tribal [their tribe] burial based solely on a deeply held belief that he is one of them. Belief-based thinking is native to primary cultures too, and is a cognitive malfunction.

Posterity would do well to value/consider all cultures, not merely

the one they were born into, and embrace what is best in

each. Science is needed for sanity (hubris being insane), not because it is said

to be but because its value is demonstrative. A sense of connection to nature, of wonder or Einstein's 'the mysterious', is the needed antidote to

exceptionalism. All cultures that have been subsumed by

the growth culture can recover and share what is best in

them that remains. Individuals must be free to learn what

is true, good, and beautiful through inquiry without being

told. Telling (or 'teaching') children what to think,

value, or how to live needs to be seen as abuse by those who were themselves similarly abused. Perpetrators and victims require belief therapy.

'It doesn't give me any satisfaction to think that my concerns will be validated by my grandchildren's generation. I would love to be wrong in everything. My grandchildren are my stake in the near future, and it's my great hope that they might one day say, 'Grandpa was part of a great movement that helped to turn things around.'' — David Suzuki

I would say the same, dittohead that I am, though my 'great hope' would differ. His is a possible future but it may not be the most likely. I can envision my grandchildren saying many things, but none are likely to think of a great movement that turned things around. I see no evidence and have no reason to think things will (probably) be turned around before the wall cometh. Humans will most likely do what they have done before. We could have hit the brakes before hitting the wall (maybe if we had slammed them on in the 1970s), but no past empire has. Even now we could slam on the brakes to not hit the wall quite so hard, but why should we be different?

Denial reigns. Still, post-peak, when humanity is looking over the precipice with an increasing number of the intelligentsia realizing that the chaos about them is closing in, when evermore realize that the dominant narrative of 'growth is good' is no longer believable, then perhaps, if they remember that those who could 'actually think more than a decade ahead' [E.O. again] had told them so, perhaps they and their public will have a teachable moment. Perhaps those in a position to say, 'we told you so', will have prepared a credible alternative based on system laws and biophysical reality. An Ecolate Party self-organizes with one mandate: to vote in enough candidates to end the Business-as-usual Party in all countries and replace all parties, countries, and humancentric laws with a Federation of Watersheds obedient to the nature of things, to natural laws, to the li of things.

It is entirely possible to imagine that among all past

empires, among the Egyptian, Indus Valley Civilization, Hittite, Canaan, Minoan, Mycenaean, Macedon, Cimmerian, Assyrian, Chaldea, Babylonian, Scythian, Sumerian, Akkadian, Achaemenid, Elam, Median, Zapotec, Lydian, Aramean, Seleucid, Parthian, Sassanid, Shang, Chou, Umayyad, Carthage, Abbasid, Greco-Roman, Median, Medes, Harappan, Mauryan, Gupta, Khmer, Jōmon, Zhou, Han, Tang, Song, Chavín, Nazca, Quimbaya, Moche, Olmecs, Tiwanaku, Mayan, Wari, Teotihuacan, Monte Alban, Great Zimbabwe, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Pitcairn Island, Cahokia, Tairona, Pueblo (Anasazi), Hohokam, Mogollon, Patayan, Fremont, Sinaqua, Paquimé, Mimbres, Pueblo Grande de Nevada, Tang, Srivijaya, Cara, Rashidun, Norse Colony (Greenland), et al. and

unknown empires/chiefdoms large and small, that there were some who foresaw things

to come and attempted to alter course. In all cases those

with a vested interest in 'staying the course' did so.

For the most part there is no evidence of a learning curve (possible exception, precolonial Tikopia and perhaps traditional Hopi.) The only clear evidence of a learning curve are the Kogi, our Elder Brothers, a functioning remanent of the Pre-Columbian Tairona civilization. The current Euro-Sino Empire is likely to repeat the damn-the-learning-curve, full speed ahead pattern, but no biophysical laws would be violated if foresight intelligence were to prevail.

The difference this time is that the empire is global. We may think that we, like some corporations, are 'too big to fail', but other bubbles have been rudely burst as history and pre-history has repeatedly shown. That a few humans may seek to avoid repeating the pattern has so far proved irrelevant.

Our best hope to avoid repeating the pattern of raise and fall (Plan B) is to be ready to install a different operating system after the blue screen appears. Develop the OS now ('information package') and expect that when there is no course to stay and growther promises are so obviously false that even the avidly oversold can't buy into them, that those grandchildren still living will have a teachable moment and be willing to upload new memes. Would a Federation OS be sellable now? No. Inconceivable. Most humans will continue to use Windows. Trying to sell Linux for free won't work. But when Windows comes up with a blue screen saying, 'Please transfer $1,433,666 to Microsoft Corp. payable in bitcoin. Press any key to continue', then an alternative OS might be sellable to the 99%.

What prevents humans from transitioning to sustainable prosperity is the default believing-mind operating system. Alternative is the inquiring-mind OS. Humans are not born with belief systems, either of a political or religious nature. An ideological world (alas, there are many competing ones, e.g. ISIS) is a dysfunctional alternative to the real one, aka Nature. Living a connected, loving life is possible. Understanding the world is a loving act. To boil it down: love and understanding are the core values for survival on this pale blue dot. The endeavor to understand what-is (science/scholarship) is alternative to ideological conceptologies (belief systems). The transition involves freeing inculcated minds and not imposing conclusions, especially firmly held ones, on children. There is a pervasive need for belief therapy. Believer heal thyself.

So my hope is not that I will be remembered for my part

in the great movement that turned things around to avert

catastrophe. Next best would be a descendant (memetic or

genetic in 10-50 years) who is sitting with friends by a wall providing

shade on a planet that had been taken and used up, and

somebody wonders why their grandparents couldn't have seen

what was coming and done something? One woman, who typically

rarely spoke, says, 'Well, my grandpa did. I went to Big

City last year and went to the library which still has the

internet thing. I used the Wayback Machine and found his

web sites. If I could go back and tell him what happened,

he wouldn't be surprised. He linked to many others who

wouldn't be either. I saw one dude lecturing thousands

about what was coming down and what needed to be done, and

thousands gave him a standing ovation. Some of them

could've been your grandparents or they must have heard

what the others were saying. So they knew or could easily

have known, but they did nothing. They cared more about

things than about us. I'm thinking we should be different,

that we shouldn't do as they did or live as they lived.

This time we'll march to a different drummer. I've been

reading and I've decided to start a new world order. I'm

calling it the Federation. You can't join, but you can be

Federation, and here's how.....'

Unfortunately, evidence is that most humans are incapable of

accepting limits, much less embracing them, at least not before hitting the wall of biophysical limits. They are programmed, along

with all other lifeforms, to embrace growth. That doing so may have a

bad outcome, including species extinction, is ignorable for a time. Humans

as social animals collectively have brains predisposed to think in terms of rights and

obligations—what one is permitted, obligated, or forbidden to do,

which leads to a violation-detection strategy: people look for cheaters

or rule-breakers and support the default norms. Such deontic thinking focuses on norms in terms of for or against which are

neither 'true' nor 'false' in terms of how science parses the words.

Normal humans are thus 'political animals'.

When reasoning about the true/false status of claims about the world,

normal people spontaneously adopt a confirmation-seeking strategy.

Beliefs as conclusions come first and are selected on the basis of what

feels good. The guiding dictum is, 'If it feels good, believe it'. Only

confirming evidence is cited and reason is used to support the

conclusion. Those with extremely high IQs, though delusional or perhaps because

delusional, are especially adept and valued. Normal humans are thus

'true believers'.

Science does not wallow in either mode of thinking, though on occasion all

scientists, qua humans, do. Science matters because it alone allows humans to

understand limits and embrace them. Most humans may not be able to

understand limits (e.g. the exponential function). They literally may

not have the capacity for it no matter how high their IQ. Some political

animals with near off-the-scale IQs may embrace the concept of limits to

growth or consuming less, but remain political animals unable to see

the (negative) implications. They may be sold on the idea that growth is

unsustainable, that being a 'growthbuster' is both thinkable and good

(superior), but they still feel compelled to avoid 'negative' thinking

about limits such that 'transitioning' to sustainability can only be

envisioned as 'preserving or enhancing' their quality of life. In the

normal public universe of discourse, a marketplace, only positive visions

sell. Only appealing products sell and overselling sells more/better. Normal humans are thus 'acquisitive consumers'.

In the current scheme of things, being none of the above —

not being a politico-believer-consumer, means three strikes and you're

out. The endeavor to find things out, however, is best done by not being

normal. Survival may be a matter of science becoming de-marginalized.

Contrary evidence, disconfirming to above, is imaginable, even if non-existent. Reverend Billy & The Stop Shopping Choir have been very effective in getting their message out there. Millions

have heard and been entertained. Some resonate with the message and

loudly declare their support, even donate money or at least buy his

books. But without a choir, strong activist community support, a website, money or

talent, what could Reverend Billy do? What if all he could do was walk

the streets and pretend he had a soapbox? Likely all he could expect

would be a 72-hour psych-hold at tax-payer expense. Still, he has

thousands of avid supporters. The research question for the grad student

is: Do those who most ardently agree with his stop shopping message

actually shop less? Is it possible, using the finest honed research

techniques available, to detect a difference in behavior between the

militant non-shoppers and a control group of equally committed consumers?

Inquiring minds want to know.

To beat the Ruskies in a space race, Americans got all pro-science, still appreciate it 'for

the milk and cheese and profit it brings' them, but in vast numbers

growthers remain committed anti-intellectuals suspicious of and ignorant

of that science thing that is currently not a cultural norm. Science as

a way of knowing remains marginalized but still tolerated as long as it

keeps the prestige and profits coming. This could be a cultural thing

and not a human genome thing. The only chance we may have of selling

limits (reality) is to await a

'teachable moment' when most humans will be open to embracing limits as

alternative to unimaginable horror or pending extinction. They may then

allow a new OS, Humanity 2.0, to be installed, as a memetic transition, which would become the new norm. A global management system for the

planetary commons (a naturocracy) would depend on specially trained humans

to make it functional by focusing on doing good science, on telling the

most likely stories to provide the firmest grasp of reality possible.

Imagine Suzuki on Easter Island during the height of the monument

building. He's walking about among all the prosperous people and asks,

'So when the last palm tree is cut down, then what?' The island is run

by political/religious animals, true believers and acquisitive consumers committed to 'staying the course', to

continued 'business-as-usual'. A few people listen to Suzuki, agree, may

form small

groups eager to hear and applaud him, but they can't bring themselves to

effectively

oppose the greater powers that be. Some may have organized protests, started a Palm Preservation Movement, and maybe a Palm Preservation Park was created (for recreational use). But.... neither archaeological nor historical

evidence survived to suggest Suzuki, or one like him, existed. But it

verges on the inconceivable that no one saw the last palm tree being cut

down and failed to see where 'progress', business-as-usual, was

heading. That no one survived who could read the rongorongo script may be viewed as a bad outcome, a far greater loss than if all 887 statues had been reduced to coarse sand by the survivors in protest.