FRIDAY, MARCH 11, 2011

A Tale of Two Islands

Sometimes some humans have a better idea

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: GROWTH, FULL SPEED AHEAD, FROM THE WIRES, REALITY-BASED, SURVIVAL ISSUES

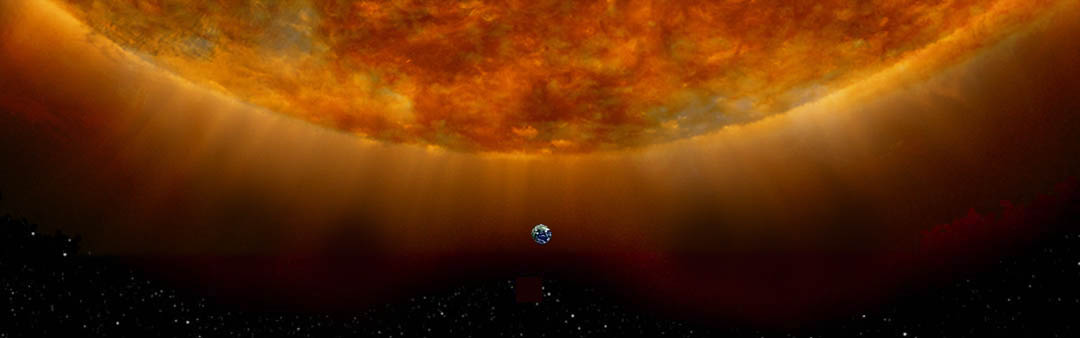

Abstract: While based on historical islands, details are imagined based on principles of systems ecology. The stories illustrate issues that arise for those living on islands, including those living on Island Earth.

TUCSON (A-P) — M.S. not found in a bottle:

Rathsi's Tale

Muzuki had taken to spending more time alone on the central mountain

where he could see the entire island and its reef below. For over a

thousand years his people, the Polynesians, had spread from island to

island, ever eastward, and Muzuki, Master Navigator, was again looking

to the east. He knew 78 islands to the west and how to navigate to each,

even the ones he had never visited, but knew of none to the east.

Several navigators before him had sailed to the furthest points of no

return—east, southeast, northeast before turning around, but had found

no new lands. Now this island was filling up; only a few trees large

enough to make voyaging canoes remained—it was time to go.

Going meant going to the point of no return and beyond. If no land

were found, all would die at sea. Few were willing to go, but Muzuki's

youngest daughter, her husband, and six other couples were prepared to

sail into the rising sun.

Overseeing the construction of the voyaging canoe, the Space Shuttle

of his culture, and its provisioning occupied Muzuki for over a year—no

detail could be overlooked. Finally, in a tearful parting, fifteen

adults, ten children, eight chickens, two bred sows, and seeds, roots,

or cuttings of all useful plants set sail to the east.

On the 43rd day, in the late afternoon, Muzuki saw a seabird flying

high towards the southeast and changed course. Three days later a speck

of island appeared on the horizon. It was a relatively large island

mostly covered in giant palm trees of a kind no one had seen before.

Soon gardens were planted and the roosters crowed.

The next year Muzuki led a voyage to explore for islands further

east; five children were born that year, but no new islands were found. The

next year they explored to the south; the oldest of the children was now

a woman and gave birth to a daughter, and no new lands were found. In

the third year Muzuki discovered a reef far to the northeast upon which

waves broke, but there was no land to settle. The home island, called

Rathsi to honor the gods, now had 20 children to call it home.

By the eighth year both Muzuki and the voyaging canoe were too old to

explore any more, and it mattered little because by then Muzuki knew

there were no more islands within reach. For now there was no reason to

go beyond the furthest horizon. It was a big island and there were now

71 rather fat people and 312 chickens living on it (the pigs had died

before reaching the island).

It was a big island for so few people, but not so big that Muzuki,

standing on the central mountain, could not see all of it. It was a

paradise of rare device, but Muzuki's thoughts were troubled. It would

be long after his death before the island filled with people, but fill

it would and there were no new islands.

On the twelfth year Muzuki called together the four clans. He was old

and he must speak. Only 24 of Rathsi's 108 inhabitants were old enough

to listen when he rose to speak. He told them that the gods had truly

blessed them in guiding them to this island of plenty, and that in his

dreams the gods had spoken to him. They said that each clan was to claim

one twentieth of the island as their own to farm, build upon, to cut

down the trees therein, to harvest the fruit, and to use as they wisely

saw fit. Also each could claim one twentieth of the shoreline and reef

to fish and harvest its bounty of seafood. Each clan could claim any

part of the island, but only a twentieth part for their use. Altogether

the people would have one-fifth of the island and the rest would belong

to the gods. The gods decreed that if anyone so much as tried to take

any part of the remaining four-fifths, all the people would be punished

harshly.

The people could not understand why the gods would speak of such

things. One-fifth of the island was far more than the people needed. But

the gods are hard to understand, and so the people honored the decree

of the gods. In the following year Muzuki helped the clans place the

boundary stones marking those portions of land and sea that the gods had

allowed the people to claim.

The fifteenth year, Muzuki knew, would be his last. For the last time

he spoke to the people. There were 154 of them now. He told all who

would listen that the day would come when their fifth of the island

would not seem to be enough. Only then would the decree of the gods be

difficult to heed.

"When that time comes some will say that it is right for the people to

take the whole island for themselves, but they must not be listened to.

The decree will be hard to follow because there will be too many people

and you will know there are too many people when they start to say

their fifth is not enough, that they need more and more. Do not listen;

say instead that the people of Rathsi must adopt new ways. Say that from

now on none can be born except by decree, and that only the death of

one can decree the birth of another. To this rule there can be no

exceptions. Do what you must to live by it. Only then will the gods

continue to favor you."

The people listened and said, “Yes, Muzuki, we will,” but few

understood. Several centuries passed, the people prospered, and in time

some began to say that one-fifth of the island is not enough. Though

Muzuki's name was well remembered, his warning was not, and so it came

to pass that those who must have more took the rest of the island and

prospered exceedingly while the gods did nothing to punish them. Muzuki

came to be known as tena'n te, “the old fool.”

Another century passed before the last of the giant palms were cut

down. Mamo had cut it down to make a fishing canoe. He and his family

prospered exceedingly when theirs was the last of the great fishing

canoes on the beach. The old ones told of other plants and animals that

had once lived on the island; the stories of the old were listened to

with bemused tolerance. There were now 13,649 proud people on the island

for they had built great monuments that would last for centuries to

come, filling the gods themselves with wonder.

But a dark day was coming. The people clamored for more, but there was

no more. Some began to take from others; their things, their food,

their land, then their lives; and the warriors, those who could take

what they wanted, ruled the island. They took and they fought; they ate

all that could not fly away, then they ate each other.

There were now 2,194 people, yet still there was not enough, still

they took and fought. They disfigured the statues of their ancestors. They

fought over the snails remaining in the tide pools and cooked them by

burning grass. The people had been punished harshly.

Aipokit's Tale

It was a small island (460 hectares, 1,137 acres), but it had never seen the footprints of

people before. Kopai the Navigator and 28 others who had survived the

fighting and the long voyage were grateful to be alive—to have come upon

a new land where they could start over. But this time, Kopai swore, his

children and their children would forever walk a different path. A

thousand islands had been chanced upon; a thousand times the people

prospered; a thousand times the fighting began—clan against clan, the

people of one island against another. A thousand times “plenty” became

“not enough.”

People and pigs had survived the voyage. Now they foraged and grew

fat. Patches of forest were cleared, gardens planted, and the people and

pigs multiplied. Kopai had seen many islands and knew how many people

and pigs there could be before tensions arose and conflict ensued. He

surveyed the small island and its reef. Eight, he thought, maybe nine

hundred people before the trouble began. He would be dead by then, but

he thought of the generations to come and of the new path they would

have to follow—and he swore that the horror he had known would not be

known again.

Twenty eight years passed, and Kopai thought and thought, and taught his

people well. There were now 108 of them, half under the age of twelve.

The pigs, with their large litters, had already become too numerous, but

the excess could simply be eaten. Already the people could see that as

the number of people increased, the number of pigs would have to

decrease, for they were eating the same foods.

Kopai had been relentless in pointing out the limits to growth on the

small island, and had led discussion after discussion about what would

have to happen when people as well as pigs reached their limit. He would

be dead, but on this small island his great-great-grandchildren would have to stop

and change course; they would have to do the hard things. The pigs could

simply be eaten, but they must never, as Kopai had often said, end up

eating each other.

And when their numbers reached five hundred they had to transition to no growth, for Kopai had thought well and taught well, and everyone

understood that if the 264 children now among them had large families,

then there would soon be too many. They understood that the horrors

Kopai had often spoke of would visit their little island if they did not

stop in time—well before the island was full.

Kopai and the other first people had laid the foundation for change. First there would be late marriages and those who would forego

marriage were honored and rewarded. As the children came of age they

were taught to pleasure themselves and the young men were given special

instruction in how to please their lover in ways that would not result

in her becoming with child. Great praise was attached to this skill—and

skilled lovers were much favored by the women who returned the favor by

hand, anus, and mouth.

If a couple wished to have a child they would announce their intent

and ask for the people's blessing—and when the number of humans must stop growing, the death of one became their

blessing. To be with child without the people's blessing was a sad

thing—knowledge of abortion had been preserved and the skill was

practiced as needed. Unblessed births forced humane infanticide. Those who chafed at such limits were encouraged to

build canoes and voyage far beyond the horizon.

In this manner the nine hundred lived, their culture evolved in wisdom

and beauty, great stories were told and retold; the three clans lived in

peace, and over a thousand years passed. Then the people did a remarkable

thing. They loved their pigs dearly but they loved one another more. One

day, by mutual agreement, they killed all the pigs.

Their skill in husbanding the resources of the island had grown over

the centuries, and now, without the pigs, there were 1,200 people living

on a tiny island, and the centuries passed.

But an evil day came upon them. Enormous canoes came from over the

horizon and brought a wealth of things the people had never dreamed of,

and with these things came new teachings. A solemn man, dressed in

black, had gathered the people together and said, "There is

only one religion, and only one way to serve God, and if you do not

embrace the right way you cannot be happy hereafter. You have never

worshiped the Great Spirit in a manner acceptable to him; but have all

your lives been in great errors and darkness." (ref)

A council was held to consider the man's words, and the man in black

was asked to leave the island, never to return. But many, especially the

young people, were fascinated by the wondrous things and wanted more.

Within just fifty years, a different man in black had built a white

house on the island for his god. He was relentless in teaching them his

new ways. He taught them to be ashamed of their sexual practices, he

taught them the missionary position and the missionary way. The practice

of abortion was the devil's work, and so they stopped. Being fruitful

and multiplying was God's work, and so they did as the others did.

Within just fifty years, everyone on the island was as children to the

men in black.

Today, there are still 1,200 people living on the island (Tikopia). Ships come and go. Things come and people go. There are now more Tikopians living off the island than on it (they export population to other islands). And of the 1,200, half may be under eighteen years of age. This suggests the Tikopians were assimilated, resistance having proved futile, even though 1,200 still have Tikopian identity memes in their heads and live on the island as other indigenous live elsewhere.

What the Aipokitans have forgotten and the men in black never taught or knew

is that we are all living on an 'island'. A great Island, one floating

in the vastness of space, but an 'island' nevertheless. What Kopai had so

long ago learned the hard way, the peoples of this Island must someday

learn again.

The expansionist culture works, but only on the leading edge of expansion (e.g. Māori who were patriarchal, ecocidal, invasive species expansionists extraordinaire before Indo-European contact). Once an island or region is taken, the expansionist culture selects for failure, and so everywhere the descendants of expansionists (the ones left behind) have had to renormalize somewhat to persist. A possibly remarkable thing about the Tikopians and Moriori is that they (perhaps starting with one leader who changed the culture) attempted to renormalize in a conscious, intentional, meta-reflexive way, with partial success, enough to persist (avoid dissolution/local extinction). The typical pattern has been to renormalize somewhat, minimally, while retaining as much of one's expansionist culture for as long as possible.

The first Tikopians, Melanesian expansionists, were forced to live like renormalizing K-strategists for 2k years until conquered by Polynesian expansionists 1k years ago who were in turn forced to renormalize enough to persist, but who again expanded when the possibility arose, such that following the coming of Indo-European expansionists in 1606, there are now six times more Tikopians than there were in the early 20th century, though 5/6ths live off of Tikopia on other islands where it is easier to import foods.

But this is not a narrative we moderns like to tell. My interpretation of the data is that indigenous cultures are all, with noted exceptions, descendants of a common expansionist ancestor that all MTIed humans share. The MTI expansion was by agro-wood-wind empowered post-Roman-dissolution Indo-Europeans who happen to be the first to exploit a planetary larder of fossil fuels to extract/produce/consume all other low-hanging fruits of Gaia.

Some indigenous cultures were forced to renormalize more than others, but with the exception of the Tairona and Muisca cultures, none consciously disavowed their expansionist form of culture such that when expansion again became possible, they refused. Compared to us modern expansionists, they may appear to be vastly less expansionistic, but this is an illusion in that they never effectively renormalized. The San (the few not yet assimilated) may have never been culturally denormalized, and the Kogi may be the only former expansionists to have conscientiously by intent renormalized such that when the opportunity to become expansionists presented itself, they refused to embrace their former ways.

In the mid-twentieth century Tikopia had a dense population that caused anxiety among the people's leaders, who feared food shortages. (In 1952-1953 a famine occurred as a result of a tropical cyclone.) In 1929 the population was about 1,270; by 1952 it had increased 39% to about 1,750.  But by about 1980, through emigration, the population on Tikopia Island had been reduced to about 1,100, while another 1,200 or so Tikopia lived in the external settlements and around Honiara, the capital of the Solomons and more on other islands. Now the substantial settlements abroad include Nukufero in the Russell Islands, Nukukaisi (Waimasi) in San Cristobal, and Murivai in Vanikoro. There is much interchange of population between the settlements and Tikopia Island. No official census data. In 1985 there were a claimed 3,320 speakers of the Tikopian language. Missionary sources claim up to 7,200 Tikopians today. Most speak English and all can use "pijin." And 98% are Christian (chief converted in 1950s), but of deep concern to some, most are not evangelical Christians.

But by about 1980, through emigration, the population on Tikopia Island had been reduced to about 1,100, while another 1,200 or so Tikopia lived in the external settlements and around Honiara, the capital of the Solomons and more on other islands. Now the substantial settlements abroad include Nukufero in the Russell Islands, Nukukaisi (Waimasi) in San Cristobal, and Murivai in Vanikoro. There is much interchange of population between the settlements and Tikopia Island. No official census data. In 1985 there were a claimed 3,320 speakers of the Tikopian language. Missionary sources claim up to 7,200 Tikopians today. Most speak English and all can use "pijin." And 98% are Christian (chief converted in 1950s), but of deep concern to some, most are not evangelical Christians.

What to do?

Consider: Island Ethics

Go back to the party