MONDAY, APR 15, 1912

Island Ethics

Earth Island as metaphor

Eric Lee, A-SOCIATED PRESS

TOPICS: ETHICS, FULL SPEED AHEAD, FROM THE WIRES, REALITY-BASED, SURVIVAL ISSUES

Abstract: Given the tales of the two islands, ethical issues that arose are considered. If carcinogenic growth is not sustainable, serving the growth SYSTEM is not ethical, posterity considered.

TUCSON (A-P) — Some of the ethical issues that arise for those living on islands were touched upon in A Tale of Two Islands. What are the issues, and do they apply to those of us living on Island Earth?

Ethics can be understood in terms of behavior—the behavior required of

responsible members of a community for its continuance. The human body

is such a community, one of cells organized as tissues and organs.

Something analogous to tolerance, respect, and cooperation between cells

are generally virtues. A "good" cell is one that performs its function,

gets along with others who do theirs, and reproduces only during the

body's growth phase or as needed to replace cells that die. If a cell

loses its functionality, we help it to regain it. Should a cell "go

wild" and reproduce at the expense of surrounding cells, we judge it to

be malignant and do everything in our power (that does not do more harm

than good) to destroy it—and as good as we ourselves strive to be, we do

what we must with extreme prejudice.

We do this because of the behavior of the cancer cells—they grow and

prosper at the expense of all around them. In the end they kill the body

and die themselves. Neither tolerance nor respect can be accorded them.

It is not the cells themselves that are bad, but their behavior. This

leaves two options if we want to avoid catastrophe: alter the behavior

or destroy the cells. In humans, behavior is often belief-based and

belief therapy the pressing need.

Note that from the point of view of the cancer cells everything looks

great right up until very near the end. What they don't see is that the

body they so enthusiastically metastasize in is growing weaker, less

functional, until it ends up in the ICU. Problems do not appear to arise

even then, from the tumor's POV, until the body starts to undergo a

cascade of multiple system failures. After all, there is still plenty of

tissue left to be consumed when the last breath is drawn. Within hours,

however, every cell is dead, including the wild cells.

If we judge this outcome to be "bad," then we should oppose the

behavior of those cells who bring it about. A major difficulty is that

there is no undeniable evidence and too few clues during the exuberance of growth that unlimited growth

in a finite system will have a bad outcome until it is too late. Can our

limited capacity for reason foresee the outcome and act in time?

Unfortunately, once the cascade of multiple system failures begins, it's

already too late. Will we stop in time? Will we reduce our footprint

(our population times per capita consumption) in a rational, orderly,

humane way? Or will we let nature do so for us in a merciless, chaotic,

and doubtless inhumane way?

On Rathsi Island, Muzuki proposed that the colonists limit themselves

to one-fifth of the island, leaving the rest untouched. This could have

been out of practical concern, such as to leave a safety margin. But if

that were the reason, why not exploit four-fifths to the maximum and

leave the rest to be used should hard times come?

Perhaps the concern is and should be ethical. Perhaps as responsible

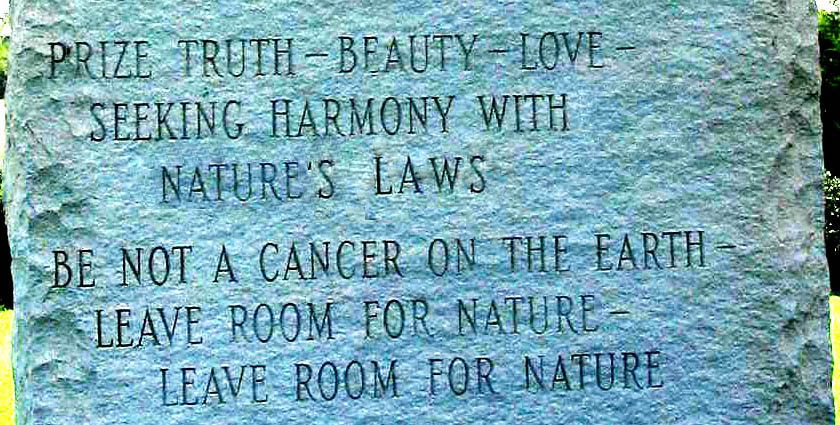

members of a community of organisms, we should not seek to grow without

limits at the expense of all around us just because we can. Perhaps

Muzuki wished to preserve the beauty and wonder of the island as complex system, knowing

that in wildness would be the preservation of his world and his

people.

Whether the people confront their limits at one-fifth or five-fifths,

they still must meet the challenge of knowing when to stop, or suffer

harshly should they fail. The difference is that if they first take the

whole island, then succeed or fail, they've left no room for

nature.

On Aipokit no room had been set aside for nature. They were careful to avoid overshoot, and the conflict and collapse that would have followed, but they chose to exploit every resource available to them. When they killed all the pigs, the same number of people could have made do with three-fourths of the island and allowed one-quarter to return to nature, but they chose to maximize people instead. They gained more of what they already had, but they gained nothing of the wildness they had already lost. If 240 people were enough, 80% of their island could have been left to the Mother. The Kogi mámas left room for the Mother.

What should we do with Island Earth? Is one-fifth of a planet enough? Those billions who think not have already voted and are clamoring for more. Can our Growth Culture be reformed? Can it be transformed into its opposite? Can the juggernaut of remorseless growth-for-its-own-sake be stopped in time? Will a tweak in the operating system be enough?

Any sustainable global society would have to set and impose limits on itself as its ethical concerns would focus on posterity. The Growth Culture, by contrast posterity-blind, focuses on maximizing individual short-term interest (self interest), as in meeting alleged needs. Whether we maximize the human presence or leave room for nature is an ethical and practical concern. Can we behave as responsible members of a planetary community of millions of species if we favor only our own existence (and that of those few plants and animals that serve us) at the expense of all other living things? Is it Self over system? or System over self?

The formula is a simple one: For any finite system, how much of it will you claim? Five percent? Twenty percent? A hundred percent? Whatever you pick, you have to know your limits. If you overshoot them, bad things happen. If you take 20 percent and fail, you overshoot and take more—bad for other living things. If you take 100 percent and overshoot, collapse follows—bad for you and the whole system. Resources are finite and the limit is set, not by population alone, but by population times per capita consumption. This is important—it's not P, it's P times C that determines our collective footprint.

If you were a member of a sustainable community, you would realize that the greater the per capita consumption is, the fewer people there can be to live and love within it. So consumption may be viewed as an ethical issue. A sustainable society can double its consumption only by halving its members. To have enough, then, would be the goal—as opposed to more and more. Those who happily consumed the least would be the most admired, the exact opposite as in the Growth Culture.

Individuals, of course, would vary in what they felt was necessary, but society would encourage individuals to examine their perceived material "needs" and help them to distinguish them from their "wants." While everyone should have "enough," everyone should also seek to discover their real needs from their illusory needs—and prefer the real to the illusory. Doing this can be thought of as "sanity" and is diametrically opposed to the business-as-usual model of overselling whatever can be sold.

If collapse comes first, if the Blue Screen of Death appears, perhaps it will be time for a clean install of a new operating system. But only those who survive can hope to do so and only if they have a new OS ready to install. This will be possible only by preparing now to both survive and rebuild (within limits). On the plus side there are no Malthusian consequences for pursuing the limits of the viable, the bearable, the equitable—of learning, loving, wisdom, creativity, harmony, truth or beauty, which, after all, are the best parts of any culture, of a life worth living.

What to do?

Read about the Cruise Ship of Fools

Read about the Time Traveler's Tale

Go back to the party